Part 2 of the book Network Propaganda studies its dynamics: the section goes into detail about how immigration came to be the central issue of the Trump presidency, but not in the way that the Republican Party expected, followed by a chapter focusing on Fox News and one on the failure modes of the mainstream media.

Political communciation, the authors argue, focuses on three mechanisms by which media influences politics: agenda setting (which questions are salient?), priming (what standards should we use to assess people or positions?), and framing (the context within which claims are made, and how that influences our understanding or attitudes). The right-wing media (successfully) framed immigration in terms of fear of Muslims, not Latin American immigration, which led to the travel ban in Trump’s first week.

As a reminder, the book is available for free online!

[Ch. 4] Immigration and Islamophobia: Breitbart and the Trump Party

This chapter discusses how immigration became the central topic of Trump’s candidacy, and how it shifted from an initial emphasis on Mexico (“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best”) to immigration from Muslim countries. To understand this, the authors take us back to the Reagan candidacy, which in 1980 embraced immigration from all over the world; the Republican Party did not contest this view.

In 1992, Pat Buchanan ran on an anti-immigrant, “America First” platform; in the early 2000s, Latinx voters moved from evenly split between Democrats and Republicans to more consistently Democratic. And after the 2012 election, an RNC taskforce emphasized that they “must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only.”

Put otherwise, the Republican Party didn’t seem to want an immigration-hostile agenda in 2016. Of course, Trump, as an outsider to the party, did not follow this playbook, and instead became the perfect candidate for the immigration “issue.” An analysis on immigration-related headlines reveals a clear emphasis on Muslim immigration and Islamic terrorism, far more than any focus on Latin American immigration, driven mostly by Trump’s candidacy (it picked up after he won the nomination).

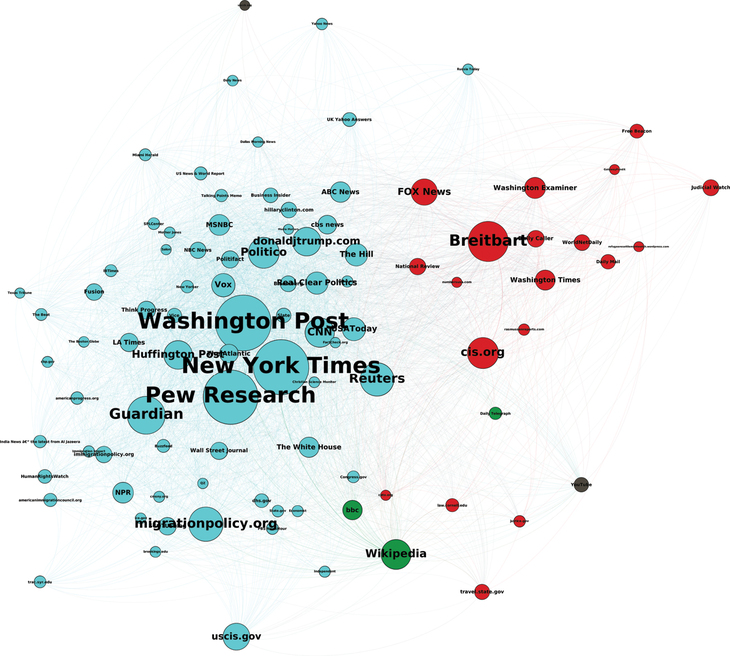

Immigration was largely Breitbart’s issue, who produced far more stories on the subject than did any other major news outlet. The following is a network map where the sizes are the number of immigration-related stories, the edges are based on inlinks, and the colors are based on the Louvain community detection algorithm:

The authors also study the influence of “explicitly white-nationalist publications” by training eight models to identify stories as white-nationalist, right, center-right, center, center-left, or left. Each had the highest accuracy in distinguishing white-nationalist stories, and had difficulty with center / center-left / left publications (supporting what we read in the first part). The use of TF-IDF revealed blatant racism and anti-semitism in the white nationalist stories.

The chapter concludes with an account of how the right-wing media (successfully!) framed the Clinton campaign in terms of corruption in the Clinton Foundation. “In the telling of the right-wing media ecosystem, Clinton was a traitor who collaborated with the enemy. And the enemy was Muslim, and mostly Arab.”

It is incredibly interesting how I, a fairly politically involved person, heard nothing about these ludicrous stories in the leadup to the 2016 election. These fantasies about Clinton being complicit in the funding of ISIS, or the Saudis bankrolling 20% of her presidential campaign, are absolutely batshit crazy. But more crazy is the fact that there is an entire media ecosystem devoted to spreading stories like these.

[Ch. 5] The Fox Diet

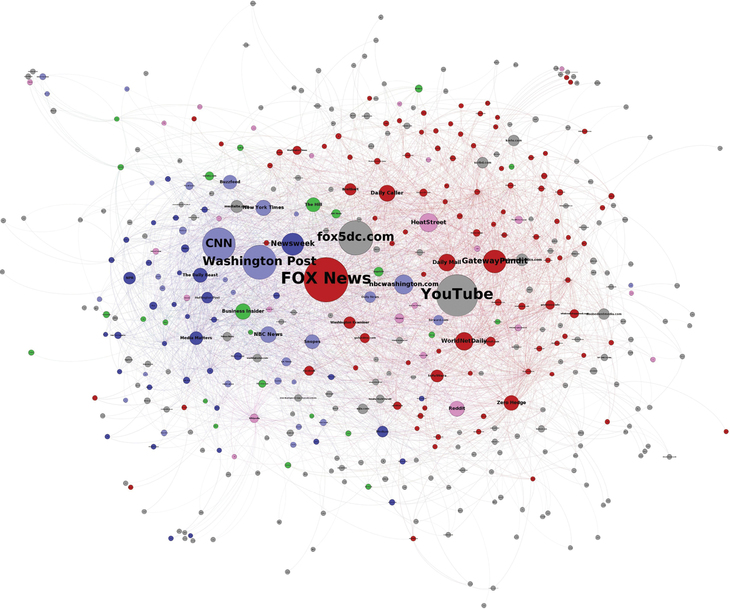

Chapter 5 consists primarily of 3 case studies of Fox news, showing how it used its position at the center of the right-wing media to support Trump throughout his controversial first year. I’ll summarize each here, then go through the conclusions.

“Deep State”: the term “deep state” was not widely used in the US prior to 2017, and when it was, it was nonpartisan. In late 2016, in response to a Washington Post article about Russian interference in the election, an Infowars video and then Breitbart story began reframing the “deep state” as a Democratic effort to portray Trump’s election as a Russian hack. Fox News picked up this term following the publication of the Steele dossier in March 2017, and it was at this point that its usage took off.

Seth Rich: Rich was a DNC staffer murdered in 2016. A year later, Fox popularized a conspiracy theory that Rich, not Russia, leaked the DNC emails, and he was murdered because of this. While demonstrably false, Fox News was positioned at the center of the media ecosystem (and criticized by CNN and Washington Post for it).

Uranium One: this case is interesting because it wasn’t just stories bouncing around the right-wing ecosystem until Fox picked them up. The New York Times published a piece titled “Cash Flowed to Clinton Foundation Amid Russia Uranium Deal,” based on an advance copy of the book Clinton Cash by Peter Schweizer. Schweizer, with Steve Bannon, cofounded the Government Accountability Institute which funded the book and was itself was funded by Breitbart investor and Trump donor Robert Mercer.

That all happened in 2015, though; it wasn’t for two years that the story reappeared. Inlinks to the NYT story started appearing in The Hill, but the real driving force behind the story became (surprise!) Fox News. Sean Hannity (to 3 million viewers) called this “the biggest scandal ever involving Russia,” in an attempt to distract from the Mueller investigation, and praised Fox for doing “what the corrupt lying mainstream media will not do.” Analysis readily reveals that the number of sentences mentioning Uranium One online was almost perfectly correlated with the number of 15-second segments mentioning it on Fox news.

In conclusion: the effects of the entire rest of the right-wing media ecosystem are, the authors argue, overstated. Fox News, on the other hand, with its millions of nightly viewers, is trusted by 65% of Republicans and the most important source of news for half of Trump voters.

This is a theme that I see a lot: people are quick to discredit TV media, saying “cable is dying” and citing their own experience reading news online. But TV remains widely viewed, and its influence is often underestimated. In the case of Fox News, it is quite dangerous:

These data warrant the conclusion that Fox shares little but a few visual trappings with the world of professional journalism at the core of the rest of the U.S. media ecosystem. It is, across its online and television properties, America’s leading propaganda outlet.

[Ch. 6] Mainstream Media Failure Modes and Self-Healing in a Propaganda-Rich Environment

This chapter studies how the mainstream media, not just the right-wing media, became susceptible to right-wing propaganda. They argue that this is due to two characteristics: balance and scoop culture.

Balance: In September 2016, Gallup surveyed Americans about what they had heard about Clinton and Trump. The results showed that “email” dominated what they had heard about Clinton, while the results for Trump were far more varied. The authors, along with Watts and Rothschild, offer a simple explanation:

A core driver of the email focus was misapplication of the objectivity norm as even-handedness or balance, rather than truth seeking. If professional journalistic objectivity means balance and impartiality, and one is confronted with two candidates who are highly unbalanced—one consistently lies and takes positions that were off the wall for politicians before his candidacy, and the other is about as mainstream and standard as plain vanilla—it is genuinely difficult to maintain balanced coverage. The solution was uniformly negative coverage.

When faced with a candidate as mired in lying and scandal as Trump, compared to a garden variety, highly qualified career politician, “emails were catnip for professional journalists.” They latched onto the emails as something negative to report on. “The search for publicly performing neutrality becomes a vulnerability that right-wing propagandists can and do exploit.”

Scoop culture: the goal of news outlets to be the first to “get a scoop” was (is) also exploitable by motivated propagandists. Hard-hitting reporting demanded eye-catching headlines, and so the Clinton Cash NYT piece reared its head again here:

The Times did not disclose Schweizer’s affiliation with Breitbart or the Mercer funding behind the book, validating him instead as a former fellow at Stanford University’s “right-leaning Hoover Institute.” The headline clearly implied corrupt deal making, while the body was more measured and included an admission, buried in the tenth paragraph, that there was no evidence of corruption.

The Times was not alone: the Washington Post was susceptible to the same dynamic. Their most popular story was titled “Emails reveal how foundation donors got access to Clinton and her close aides at State Dept.” The first paragraph is equally salacious, and it’s not until the 16th paragraph that they write that the Clinton aides refused inappropriate requests.

The AP did the same, publishing on Twitter “BREAKING AP Analysis: More than half those who met Clinton as Cabinet secretary gave money to Clinton Foundation.” This was later debunked, but the story had already circulated broadly.

Self-healing: with all of this said, every news organization makes mistakes. “Central to the practice of objectivity as truth seeking is not infallibility but institutionalized error detection and correction,” the authors write. They study the recipients of Trump’s 2017 Fake News Awards, finding that in all cases but one, the media outlets who published stories later found to be false retracted them quickly after learning the truth. A driving force behind this was mainstream outlets constantly checking, and occasionally correcting, each other.

Rather than circling the wagons, in most of these cases news organizations exposed, admitted, and corrected errors over very short timelines, through both internal processes and network processes of mutual monitoring. The dynamic is fundamental to error avoidance, detection, and correction in a well-functioning media ecosystem and is exactly the opposite of the mutually reinforcing roles that entities in a network subject to the propaganda feedback loop exhibit.

Closing thoughts

Man, this book is dense. I’ve been averaging a chapter a week, and each will take an hour or two to read. That’s not to say that it’s badly written, but it is a challenging read; my next book will be something lighter.

This was a really interesting section. I found the discussion in Chapter 6 to be most eye-opening: I’ve understood how the mainstream media operates in terms of truth-seeking and self-correcting, but I never thought about the failure modes of those dynamics. That also explains Sanders’ quote that “the American people are sick and tired of hearing about your damn emails”—that was what the media latched onto, and in an attempt to be “balanced” they had little else to talk about.

It wasn’t a surprise to me that Fox is the primary propaganda agent in the US, nor that Trump’s campaign embraced immigration as the central issue, but it is instructive to see how these dynamics play out in practice. Understanding Fox’s role as an amplifier on the right is, I think, key to making sense of what happened in the media.