Data work is foundational to any AI application, but often undervalued. In practice, this results in “data cascades,” which occur when data issues compound into downstream technical debt. This work studies how data cascades happen, what they cause, and how to avoid them.

Link: Google Research website

Authors: Nithya Sambasivan, Shivani Kapania, Hannah Highfill, Diana Akrong, Praveen Kumar, Paritosh Lora Mois Aroyo

I don’t actually remember where I found this (Twitter?), but it looked excellent. This work will appear at CHI 2021.

Background and motivation

Data work is foundational to any AI application. Data has to be collected, curated, understood, and prepared in advance of any kind of model training or advanced analytics. Data also isn’t neutral or raw:

There is substantial work in HCI and STS to establish that data is never ‘raw’, but rather is shaped through the practices of collecting, curating, and sensemaking, and thus is inherently sociopolitical in nature.

But data work is consistently undervalued. Human work to curate or label data is often seen as menial or repetitive (look no further than Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for an example!), but is in fact “complex, skillful, and effortful.”

This paper studies how issues with data work can turn into data cascades. It focuses on high-stakes machine learning systems that are deployed in production. The authors interviewed 53 AI practitioners in the US, India, and East and West Africa, and 92% of them had experienced at least one data cascade.

Defining data cascades

We define Data Cascades … as compounding events causing negative, downstream effects from data issues, that resulted in technical debt over time.

Some other characteristics of data cascades:

- they are opaque; there are no clear indicators to detect or measure their effects.

- they are triggered when “conventional AI practices are applied in high-stakes domains”.

- they have negative impacts (community harm, relationship burnout, costly iteration, discarding datasets)

- nearly half of projects experienced two or more cascades

- they are often avoidable!

That makes sense. The authors found from the interviews that this is often due to misaligned incentives:

An overall lack of recognition for the invisible, arduous, and taken-for-granted data work in AI led to poor data practices … Care of, and improvements to data are not easily ‘tracked’ or rewarded, as opposed to models. Models were reported to be the means for prestige and upward mobility in the field.

Other factors included deadlines and other constraints getting in the way of improving data quality (“we’ll do it later”), difficulty getting buy-in, clients expecting “magic” from AI without care for the data, and lack of education on how to clean or collect data.

Real-world causes of data cascades

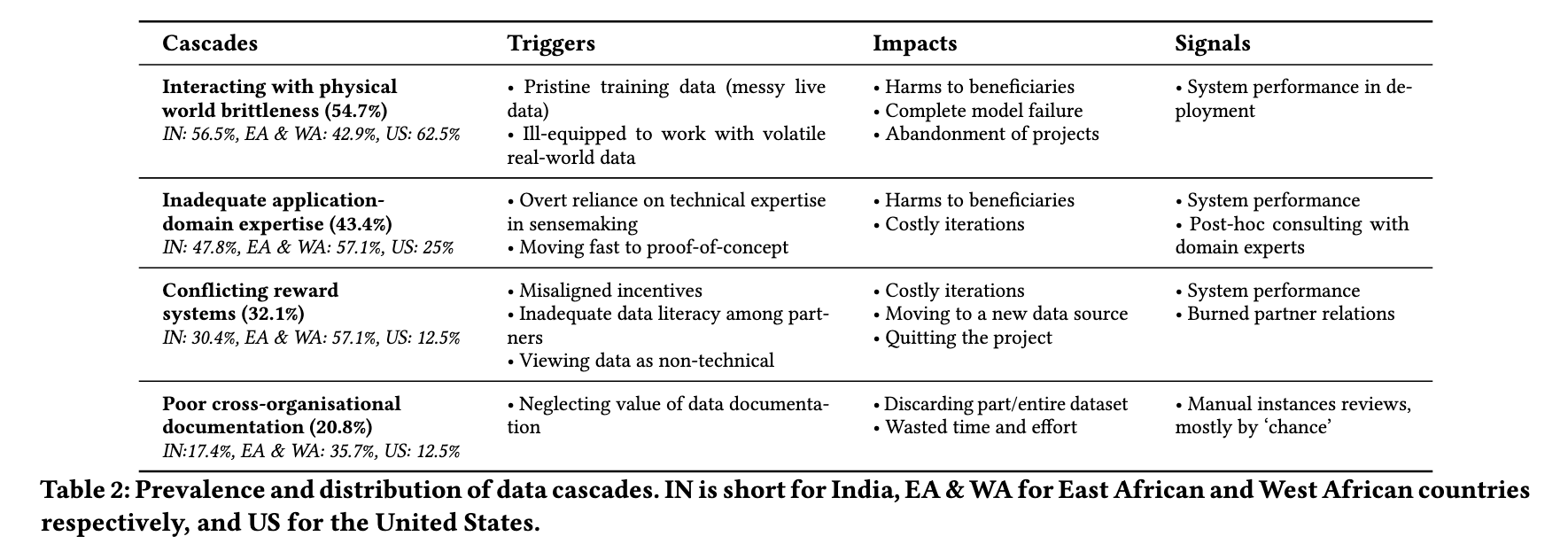

This table does an excellent job of summarizing causes, impacts, and signs of data cascades:

Particularly interesting to me is the class of data cascades caused by “interacting with physical world brittleness.” In high-stakes domains especially (perhaps because “high-stakes” feels similar to “real-world-impacting”), changes in the real world often caused deployments to break.

Some examples of events that caused data cascades include:

- rain and wind moving sensors placed in the wild

- a drop of water on a camera causing an image to become blurry

- changes in banking regulations affecting data capture

- lack of domain expertise to deal with subjectivity

- ground truth being inaccurate (in e.g., insurance claims, where historical data itself has bad decisions)

It’s worth a reminder that data collection is a really hard problem. “When a clinician spends a lot of time punching in data, not paying attention to the patient, that has a human cost,” one participant said. That’s absolutely true, and real discussion of the costs and tradeoffs of different methods of data collection is needed. Too often is data taken for granted.

Towards data excellence

What are we to do? The paper offers many suggestions. From the discussion:

Our results indicate the sobering prevalence of messy, protracted, and opaque data cascades even in domains where practitioners were attuned to the importance of data quality. Individuals can attempt to avoid data cascades in their model development, but a broader, systemic approach is needed for structural, sustainable shifts in how data is viewed in AI praxis. We need to move from current approaches that are reactive and view data as ‘grunt work’. We need to move towards a proactive focus on data excellence—focusing on the practices, politics, and values of humans of the data pipeline to improve the quality and sanctity of data …

The authors go into more detail about this idea of data excellence, which broadly means improving the quality and “sanctity” of data, through proper infrastructure, interventions, incentives, and more.

They bring up Rachel Thomas’ Reliance on metrics is a fundamental challenge for machine learning as an example of how we need to move from “goodness-of-fit to goodness-of-data,” which feels a little cute, but is certainly true. How representative is a given dataset of the real world thing it’s trying to capture? It’s hard to know, and we definitely don’t have any metrics to assess this.

There are few incentives for this excellence, and the authors discuss how this has to change. Data is viewed as operations work; publications are mostly on models, where the datasets are clean, curated, and static; “dataset papers” are relegated to separate tracks in conferences.

HCI has a role to play here, too:

Learning from HCI scholarship on ways to recognise the human labour in preparing, curating, and nurturing data that powers AI models, among crowd workers, office clerks, and health workers can be helpful.

I’m reminded of Niloufar Salehi’s We Are Dynamo as an example of how to give more power to crowd workers, who often do tons of labor for researchers.

More immediately, creating tighter feedback loops can help avoiding data cascades. The teams with the fewest cascades “ran models frequently, worked closely with application-domain experts and field partners, maintained clear data documentation, and regularly monitored incoming data.” Remember, these are avoidable.

With that said, current work in data analysis focuses a lot on “distributions and wrangling,” and less on upstream (defining requirements) and downstream (monitoring live data & measuring impacts) interventions. Better tools for observing, curating, and labeling data are needed, both during collection and in production.

My thoughts

Reading HCI papers about real-world machine learning is always interesting to me. That’s what I do, and it’s a fun exercise to see where my experiences do and do not align.

This paper ended up being an unexpected formalization of something I experience often. At my last job, data issues were constant, and it was mostly due to underinvestment in data infrastructure and early-stage data work. But I had not considered the idea of a “cascade,” even though that’s clearly what happened—data issues always got worse over time.

I also think that data cascades are a higher-level concept than what I had in mind starting the paper, which was closer to the more mundane “this column has unexpected nulls!” that can carry through a project. That, though, is itself caused by the kinds of data cascades discussed here.

It’s no surprise that model work is seen as more desirable and more important than data work. The job market reflects this, with tons of people wanting to do data science or machine learning, but fewer the more foundational (and more in demand) data engineering. Conference publications reflect this too, as the authors note.

This helps affirm my decision to switch out of a data science role. As the paper mentions, I think many of the core problems data scientists face are best handled before they ever reach data science. The reality of data science work was mostly dealing with data cascades, anyway—why not work in a role where I can actually try to solve them?

I think this was an excellent paper. It captures a lot of parts of (and problems with) the everyday data science experience. The diagnosis of how data cascades happen was, in my view, spot on. The solutions, of course, are harder.