What do you do when “hit a company where it hurts” means their data, or their models? What does it mean to go on a “data strike”? This paper studies the idea of withholding one’s personal data and evaluates its impact on recommender systems.

Authors: Nicholas Vincent, Brent Hecht, Shilad Sen

Motivation

“Data is the new oil,” right? Companies are collecting more data than ever before, and increasing their power and profits as a result. And yet this data is (usually) rooted in people’s behavior. Some academics call this kind of work “data labor.”

What happens if this labor is withheld, in the same way that traditional labor is?

From the abstract:

The public is increasingly concerned about the practices of large technology companies with regards to privacy and many other issues. To force changes in these practices, there have been growing calls for “data strikes.” These new types of collective action would seek to create leverage for the public by starving business-critical models (e.g. recommender systems, ranking algorithms) of much-needed training data.

Starving models of training data (or potentially providing garbage training data, which might be worse?) is certainly an interesting form of collective action. This paper focuses on recommender systems, and simulates data strikes to understand their possible effects.

Outline

This paper studies:

- where data strikes sit relative to traditional boycotts, and collective action more generally

- the extent to which a data strike on “surfaced hits” can affect a recommendation model

- how data labor power adds to standard consumer power

- how data strikes have a lower barrier to entry than boycotts.

Let’s dive in.

What are data strikes?

Technology companies are not immune to traditional collective action. In June, Facebook employees staged a walkout to protest the platform’s handling of President Trump’s posts. Gig workers from various companies held a strike to demand better virus protections in May. And calls to boycott Amazon are seemingly never ending.

But data strikes are different, this paper claims. Calls for data strikes use various framings of “data as capital” or “data as labour,” suggesting that individuals should more frequently take advantage of leverage they have because of their data.

How might people do this? One example is through deleting their data (which GDPR has mandated that companies allow). Or perhaps by trying to mess with domains where there is no data yet (a new Netflix show being released).

The fact that recommender systems can be manipulated is not new. One known vulnerability is shilling, where a system is flooded with positive reviews to promote a particular item. Shilling isn’t a data strike, but similar ideas apply, the authors claim.

A framework for data strikes

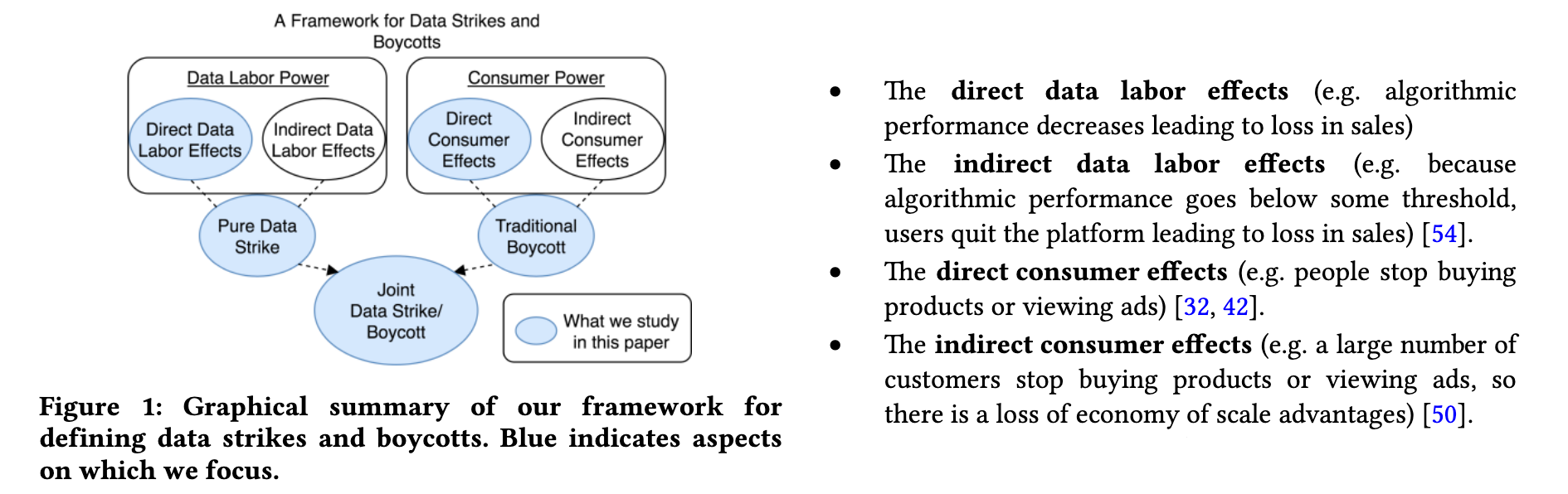

The authors place data strikes into a broader collective action context.

They first cover the difference between strikes and boycotts. In boycotts, consumers cut off an asset (e.g., money). In strikes, laborers do. (This difference was in the spotlight during the recent NBA strike, which was incorrectly called a boycott in many places online.)

Data strikes are different.

In most cases, boycotts against tech companies implicitly include a data strike.

If you boycott YouTube, you starve them of (however little) data on your viewing habits. If you boycott Amazon, they lose out on data on how effective their recommendations or search are, or on potential reviews. (Note that this only makes sense with the context of “data is labor.")

However, it is often possible to participate in a data strike without boycotting the platform.

Refusing to review a product on Amazon is a data strike. Browsing YouTube in incognito mode is a data strike (you know what you’re interested in, but Google can’t use recommendations to help get you there).

This gets us to a compelling figure that organizes these ideas:

Experimental study

The authors used the standard MovieLens dataset with SVD and KNN recommender algorithms. (Their code is open source!)

They simulated two kinds of data strike campaigns:

- General campaigns, where a random proportion of users (from 0.01% to 99%) participate

- Homogenous campaigns, where a “similar” group of people participates (in terms of demographics, being a fan of a specific genre, or having different rating behavior). In these cases, only 50% of the population (of “all women” or “all comedy fans”) participated.

One interesting problem is that traditional evaluations, which are focused on the quality of recommendations for users who receive them, will break down in the case of a boycott. They introduce a new metric called surfaced hits, which essentially asks “what proportion of the user’s choices were surfaced by the recommender algorithm?” The idea is that a perfect recommender algorithm will always show the user content that they will later click on.

Results

This post is getting pretty long, so I’ll be brief. (Once again, I find the problem setup and experimental design to be far more interesting than the results.)

With general boycotts and data strikes:

- Boycotts are substantially more effective than data strikes.

- However, small changes in recommender system performance can have enormous bottom line impacts at scale.

- Increasing the number of users (but having the same % strike) decreases the effectiveness of the data strike.

- A change in surfaced hits has a non-linear value to recommender system operators.

A strike with 30% of users (which is a realistic size based on research on political consumption; see Related Work) degrades performance such that users lose roughly half the benefits of personalization.

With “homogenous campaign group” experiments:

- When homogenous groups of people strike, non-striking users with the same characteristic will be more affected than others.

- Some groups are better able to affect non-striking users than others, and this is not a function of size. (Maybe it’s a function of how holistic the characteristic is.)

Discussion

The takeaway: This paper clearly showed that data strikes and boycotts can have meaningful impacts. They’re also more accessible than traditional collective action, though this comes with having a lesser impact.

On simulations: I love papers that propose an idea and then use a simulation to explore it. While simulations are necessarily incomplete, they can still be powerful tools for studying new ideas. The authors demonstrate this in the barrage of experiments that they run: they vary the fraction of users participating, the compositions of striking groups, the dataset size, and the algorithms themselves.

Potential negative impacts: This paper dedicated a couple paragraphs to discussing these, and I greatly appreciate this. They highlight two concerns with this work:

- Companies could simulate this problem, too, and find out which groups of users are useful to their algorithms to justify ignoring their demands. (I am fairly certain that those would be people of color, women, or other marginalized groups, too.)

- This relied on the MovieLens dataset, but companies with their own data assets will necessarily have an advantage in this space.

The main questions I have are on extensions to this work. What happens if people try to flood the system with bad data, by choosing items they’re not interested in or selecting items randomly? Can these make a difference to recommender performance? What happens outside recommender systems, e.g., for news feeds?

Data strikes are a new form of collective action, and I appreciate this work exploring this relatively recent concept. The data isn’t all, though; powerful algorithms operate on this data, and so in a way this problem is one of finding out how best to degrade algorithmic performance. I’m excited to see how this work develops over time.