Explainable AI is often treated as an algorithmic problem, but this framing leaves a blind spot of how an AI system fits into an actual organization. This paper uses the idea of social transparency to motivate a new, more practical framework for thinking about explainability.

Authors: Upol Ehsan, Q. Vera Liao, Michael Muller, Mark O. Riedl, Justin D. Weisz

Link: arXiv; to appear at CHI 2021.

Background and motivation

Many approaches to explainable AI take an algorithms-first perspective, searching for technical solutions and methods. “What’s a linear approximation to this opaque algorithm? What features helped this model make its decision?”

Notably, this approach is different from how humans typically view explanation. Explanation, the authors write, is a “shared meaning-making process that occurs between an explainer and an explainee” (emphasis mine).

Explanations in human-human interactions are socially-situated. AI systems are often socio-organizationally embedded. However, Explainable AI (XAI) approaches have been predominantly algorithm-centered.

One of the papers I read from CHI 2020, Interpreting Interpretability by Kaur et al., studied how data scientists use interpretability tools in practice. They found that people generally viewed interpretability as being “unidirectional, with tools providing information to user.” This reflects what the authors here call an algorithm-centered approach, and is in contrast to the between-ness that sits at the heart of explanation.

The authors continue:

Given this understanding, we might ask: if both AI systems and explanations are socially-situated, then why are we not requiring incorporation of the social aspects when we conceptualize explainability in AI systems? How can one form a holistic understanding of an AI system and make informed decisions if one only focuses on the technical half of a sociotechnical system?

That’s a compelling argument! This paper (if I understand correctly) argues that explaining AI in purely algorithmic terms misses the point. If we’re thinking about explainability in AI, we must also consider the broader socio-organizational context. The authors call this social transparency (ST).

Incorporating social transparency

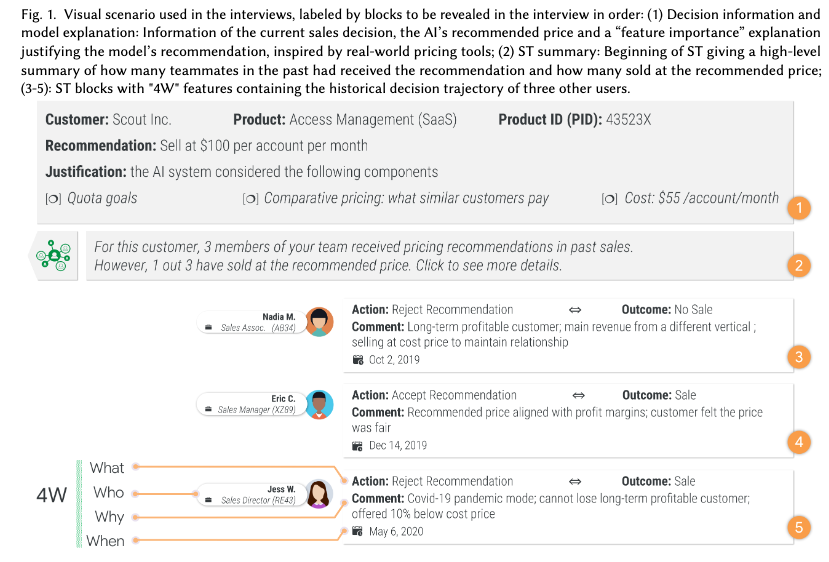

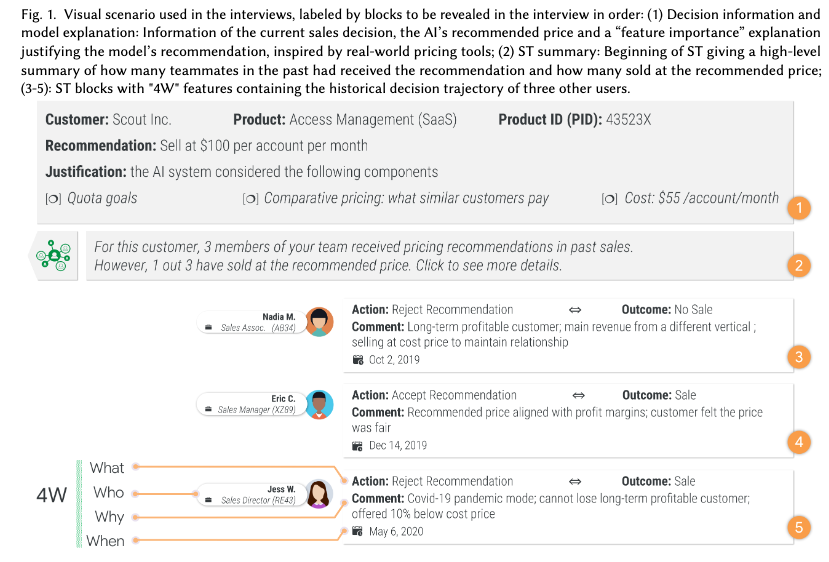

Given all of the above, the goal is to rethink our understanding of explainable AI to incorporate social transparency. After pilot studies, the authors landed on a 4W framing here: “who did what with the AI system, when, and why they did what they did.”

To study this, they construct a situation where an AI model is providing price recommendations to salespeople. They created a visual aid to contextualize the model, explain its recommendations, and show past decisions made by other salespeople.

The paper notes that the sales setting is broad enough to engage people who don’t work in sales, while also helping people to explore the transferability of ST to other domains. I’m personally convinced by this; this seems like it could be useful in, say, an ML-driven context moderation setting or another human-in-the-loop scenario.

The authors used this scenario and visual aid for 29 semi-structured interviews. These consisted of discussions about explainable AI, a run of the sales scenario described above, brainstorming on social transparency, and discussions of possible negative consequences of social transparency.

Findings

Perhaps the most important finding is the one that validates the need for this research paper: that technical transparency is not enough for making complex decisions. Many participants noted this in many different ways.

There is a shared understanding that AI algorithms cannot take into account all the contextual factors that matter for a decision: “not everything that you need to actually make the right decision for the client and the company is found in the data” (P25-NS). Participants pointed to the fact that even with an accurate and algorithmically sound recommendation, “there are things [they] never expect a machine to know [such as] clients’ allegiances or internal projects impacting budget behavior” (P1-S). Often, the context of social dynamics that an algorithm is unable to capture is the key: “real life is more than numbers, especially when you think of relationships” (P12-NS)

The authors expand on this by labeling three types of context: technological, decision, and organizational. This is best explained through the table that I’ll lift from the paper:

Technological context helps to calibrate trust in the AI system. Decision context can expose “crew knowledge” (often referred to as “tribal knowledge,” but the authors chose a better term) and build confidence in making decisions. Organizational context can help an individual to understand the broader organization (including teams, norms, values) by making visible what people have done in the past.

What challenges can ST create?

Happily, the authors studied challenges and tensions that might arise from social transparency. One challenge is that privacy is at odds with transparency. Participants worried about revealing personal information (accidentally or because they were compelled to), or that they would make themselves visible to others unnecessarily.

Another (my main concern) was bias. Seeing a record of past decisions made feels like it might induce an organization-wide game of “follow the senior leader” or “do what everyone else did.”

Others included information overload (if the number of past entries became too large) or a lack of incentive to contribute to an ST system.

My thoughts

I enjoyed this paper. I particularly appreciated the practical grounding for this project. The author, Upol Ehsan, expanded on this in a Twitter thread:

Some backstory- years of fieldwork built the foundation for this work. During a cybersecurity project, I noticed how despite great algorithmic transparency of an XAI threat detection system, no one got value from it. It was clear that algo transparency alone wasn’t enough.

My experience in industry—though by no means representative—has left me skeptical of explainable AI. It feels like people rarely care about it, and because of this paper I see that this is probably because explainable AI doesn’t actually solve any organizational problems.

This, the authors note, is largely because “the epistemic canvas of XAI has largely been circumscribed around the bounds of the algorithm." XAI is framed as a question about a technical model, not a sociotechnical system. But the very act of explanation is a “people problem,” meaning that technical solutions alone cannot possibly be enough.

The introduction of this paper was challenging for me to get through. I think the sales scenario is far more compelling than the epistemic discussion about what “explanation” is. Perhaps that’s because of my position in industry; nonetheless, it feels almost ironic that a paper about practical challenges with XAI doesn’t more strongly motivate itself with those very challenges and instead treats this conversation as an abstract and epistemic one.

I don’t think this is an AI problem

Finally, I think this work is more broadly applicable outside AI to general software systems.

Earlier today, I ran into a bug where one of our tables didn’t have any data beyond December 1, 2019. Treating the table as a model, and the ETL pipeline as the “training process,” one could imagine whether or not I should “trust the table.” If I did, I’d have been sunk—needing to refactor our data pipeline or figure out some kind of workaround.

Instead, I asked for help. I asked if others had used this table before, or were possibly familiar with its quirks. The knowledge of who to ask—“these are the people who might know something”—only existed in my team’s head. (There was a contact person listed in our data catalog, but my team knew that historically those contact listings were rarely useful.)

My questions were ones addressed in this paper: “Has anyone seen this happen before? Is there more information I’m missing?” An ST-based system that addressed how this table functions in the broader data science organization would have been quite useful to me.

This, honestly, is why machines will never replace data science and engineering. No machine is capable of plumbing through the depths of the organization to figure out who to ask for help here. The process that led to the creation of this table was blind to the issues that will arise from the table’s use.

I enjoyed this paper. I appreciate the look into the practical challenges with XAI, and think that the social transparency framework is promising. I look forward to a day when XAI is treated as the sociotechnical problem that it is.