What does it mean for a human to trust an AI system? What are the requirements for it to be present, and how do we know if it is? This paper, which just appeared at FAccT, explores these questions.

Authors: Alon Jacovi, Ana Marasović, Tim Miller, Yoav Goldberg

Link: arXiv; from FAccT 2021.

Background

“Trust” is often a desirable property of interactions between people and AI, and it underlies the desire for explainable AI. But what does trust actually mean? What is a human trusting an AI model with? What are the prerequisites to building this trust?

The abstract summarizes how the authors will explore trust:

We discuss a model of trust inspired by, but not identical to, sociology’s interpersonal trust (i.e., trust between people). This model rests on two key properties of the vulnerability of the user and the ability to anticipate the impact of the AI model’s decisions. We incorporate a formalization of ‘contractual trust’, such that trust between a user and an AI is trust that some implicit or explicit contract will hold, and a formalization of ‘trustworthiness’ (which detaches from the notion of trustworthiness in sociology), and with it concepts of ‘warranted’ and ‘unwarranted’ trust.

My post here will mirror the structure of the paper.

Defining trust

The authors ground their definition of human-AI trust in sociology. In one formulation, “if A believes that B will act in A’s best interest, and accepts vulnerability to B’s actions, then A trusts B.”

Vulnerability is associated with risk. Being vulnerable requires accepting the risk in trusting someone else. (This statement has nothing to do with AI—that’s what that means in interpersonal relations.) That applies to AI, too.

What about anticipation, though? In this context, anticipation means “believing that the other will act in your best interests.” But what specifically does a human anticipate from an AI? That its decisions are correct, or unbiased, or deterministic? The authors frame this as part of a bigger discussion about contracts.

Correctness and contracts

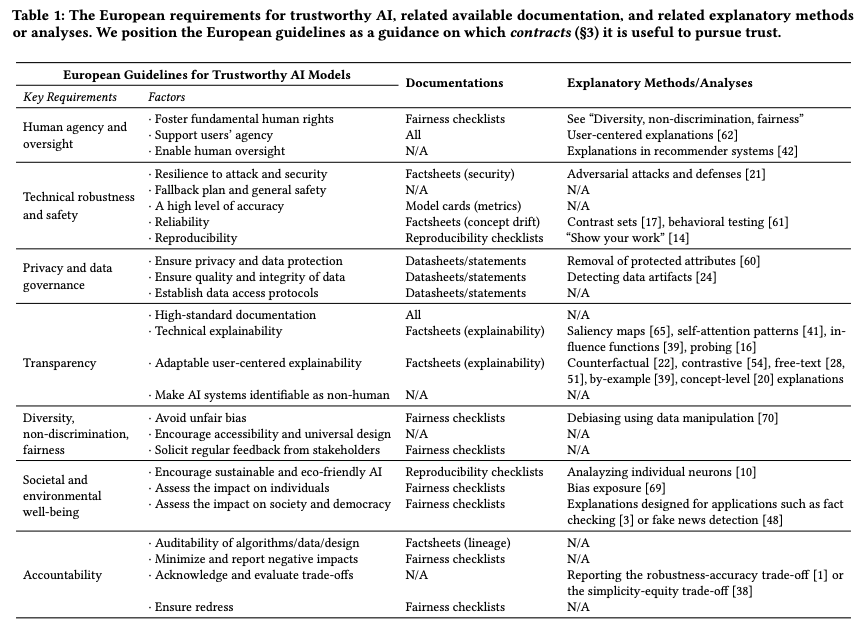

Model correctness is a general case, they write, of contractual trust. This is the belief that a trustee will stick to a specific contract, e.g., of transparency, reproducibility, or privacy. They include a table from the European Commission on trustworthy AI and use it to provide examples of how to increase contractual trust:

“An AI model is trustworthy to some contract if it is capable of maintaining this contract,” they write. If you trust an AI model, you believe that it will uphold some contracts.

The authors are careful to distinguish trust (an attitude of a person) from “trustworthiness” (a property of an AI model). One can trust an untrustworthy model, and one can be untrusting of a trustworthy model. They call trust warranted if it’s the result of trustworthiness, and unwarranted otherwise. When pursuing trust, we should obviously pursue warranted trust, but we should also minimize unwarranted trust.

Building trust in AI

The authors ask: “What causes a model to be trustworthy? And what enables trustworthy models to incur trust?”

Intrinsic trust is built when a model’s observable decision process aligns with a user’s beliefs. This requires a user to understand the decision process and for them to have prior beliefs. To build intrinsic trust, then, understand who your users are and frame the model’s decision-making process in a way that they can understand.

Extrinsic trust is built through evaluation of results. This requires trusting the evaluation scheme (that it used an appropriate metric, that the training data distribution matches the unseen future data, etc.), and the authors go into detail about how this must happen.

And so the authors extend a common claim in explainable AI (XAI) from:

XAI for Trust (common): A key motivation of XAI and interpretability is to increase the trust of users in the AI.

to:

XAI for Trust (extended): A key motivation of XAI and interpretability is to (1) increase the trustworthiness of the AI, (2) increase the trust of the user in a trustworthy AI, or (3) increase the distrust of the user in a non-trustworthy AI, all corresponding to a stated contract, so that the user develops warranted trust or distrust in that contract.

This builds on all the concepts presented previously, which makes it a nice summarization of the paper. Make AI more trustworthy, make people trust trustworthy AI more, and make people distrust non-trustworthy AI more. This all occurs with respect to a contract of performance, fairness, privacy, or something else.

The main contribution here is defining previously-fuzzy trust-related terms. What does human-AI trust mean? What is required for it to exist? When is it warranted (and what does that mean?)? The paper answers all of these.

My thoughts

I find the discussion of warranted vs. unwarranted trust to be interesting. It didn’t occur to me that one can design around a lousy AI model to make it appear trustworthy, but in hindsight this is obvious. Providing a sleek interface or explanations can build trust in a model without requiring the model itself to be trustworthy. People dress up bad software every day.

The authors frame this as an ethical issue, which I agree with. “In this work, we assume that it is a core motivation of the field to remain ethical and not implement or prioritize unwarranted trust.”

Unwarranted trust reminds me of the CHI paper, Interpreting Interpretability by Kaur et al., which showed how data scientists overtrust interpretability tools. Misapplying interpretability tools is a great example of how to (unethically) build unwarranted trust in a model.

I liked the discussion of how human-AI trust differs from human-human trust. In human-human trust from sociology, trust is justified if it was not betrayed. (I’m sure this is an oversimplification, but I’m no sociologist.) For human-AI trust, though, trust is justified if the trustee is trustworthy to some contract.

The human-AI definition is stricter. If a trustee catches a cold and can’t fulfill their promise, but in principle could, it’s difficult to assign blame. But this doesn’t apply to AI. An AI’s capabilities are well-defined and it does not have intent. Its trustworthiness can only be evaluated at the face value of its actions.

This reminds me of the Stochastic Parrots language models paper, which drew a distinction between language that comes from humans (a two-way act of communciation with intent and nuance) and language that comes from language models (which is just text).

The Stochastic Parrots paper provides an example of why trust in AI must be different from trust in humans. If a human says something harmul, they have the opportunity to clarify their intent and restore trust that would have otherwise been broken. A language model that produces harmful text has no intent. It can only be evaluated based on its outputs.

I liked this paper overall, but had trouble wrapping my head around some of the more abstract concepts discussed here. I think it will help me to see future work that cites this. I think I agree with their formulation of trust, but don’t really know enough to critique it, so I look forward to reading more in the future.