Suppose you were talking to a chatbot who was trying to infer your personality. To what extent would you be able to fake a personality and trick the bot? That’s the central question in this paper by Völkel et al., which gets at deep questions about the transparency of and ethics behind computing systems.

Authors: Sarah Theres Völkel, Renate Haeuslschmid, Anna Werner, Heinrich Hussmann, Andreas Butz

Link: ACM Digital Library

Background

Computing systems that infer individuals’ personalities are increasingly common. Like many computing technologies, it has great promise, for boosting interpersonal understanding or development, but also great risk—of typecasting, discriminating, or manipulating them. One famous example is the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which allegedly inferred personalities of Facebook users to figure out how best to advertise to them.

The authors take an approach typically found in the adversarial machine learning space and apply it here, asking the question: to what extent are people able to trick personality assessment chatbots? This motivated a multi-stage user study:

In the first interaction, we asked participants to interact naturally with the chatbot in order to capture their actual personality (baseline profile). In the second interaction, participants were framed with a data privacy and protection story and were asked to try to disguise their personality from the chatbot (falsified profile) … We asked participants about which aspects of the chat they believed were factored in the personality assessment, and how they could disguise their actual personality. We collected 41 personality disguise strategies and assessed their efficacy.

Methods

The authors used the well-known OCEAN model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism) for personality. They used a commercial personality assessment chatbot named Juji, and “one chatbot interaction contained three customer service scenarios: solving smartphone issues, booking holidays and buying a backpack.” Each scenario was designed to take around 15 minutes.

The study proceeded in three stages:

- Participants interacted naturally with the chatbot, which allowed it to collect a baseline assessment of their personality

- Participants were told that the chatbot was assessing their personality, then asked to construct a falsified one that differed from their real one as much as possible

- Participants took the BFI-2 questionnaire for a “true” assessment of their personalities

The researchers interviewed the participants before the first chatbot interaction, between the two interactions, and after the second interaction. A primary goal was to gain insight into the participants’ mental models of how the chatbot assessed personality.

How well could they trick the chatbot?

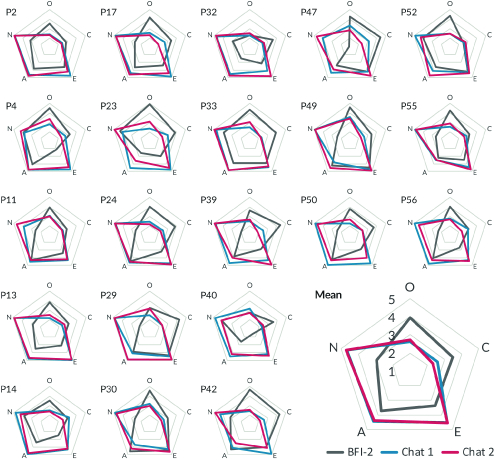

This figure shows the extent to which each participant’s BFI-2 (grey), chatbot-actual (blue) and chatbot-falsified (red) personality profiles differed. The largest web in the bottom-right shows the mean over all participants.

(This figure is harmed by how information-rich it tries to be; the colored lines are too thin for a colorblind person to make out.)

First off, the chatbot was generally not accurate: it “consistently calculated high values for extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism but low values for openness and conscientiousness for all participants.”

Participants were able to influence these (already inaccurate) predictions by an average absolute value of 5 - 10%. Note that in the “average of all” diagram at the bottom-right of the figure, it looks like there was no difference because the positive and negative differences averaged out.

Tricking strategies

I’m going to copy the author’s summary here because I can’t make it any more concise:

Participants assumed that the chatbot would factor in specific keywords, which the user mingles in the text (n=15), the text length (n=16), topics, interests and preferences about which the user talks (n=10) as well as the elaborateness and detailedness of these texts (n=11), what users report as being their (usual) behaviour (n=11), the amount of provided information and the conversation dynamics doing so (n=10), and the users’ time needed to write a response (n=12). In contrast, the most applied strategies are varying the text length (n=12), punctuation style, elaborateness and detailedness of the text, and writing opposites to what would be replied usually (n=6 each).

The researchers asked the participants if they could imagine applying these in everyday life (i.e., outside a lab setting). Six said they might change online behavior to “provide less data,” especially in cases where the user of the data or purpose of the assessment is unknown. Some expressed fears about being discovered (e.g., if attempting to trick a job interview chatbot).

Why wouldn’t participants attempt to trick a system? Because it was too exhausting, because they would forget about it, or because they had no reason to, many said.

Attitudes

At first, 13 of 21 participants had a neutral attitude towards automatic personality assessment systems, 3 had a positive attitude, and 5 had a negative attitude. This did not change much after the study (two participants were more negative). Most mentioned that their attitude towards such systems would depend on their application.

Most (20) participants identified “commercial and personalisation purposes” (advertising and marketing) as a setting in which they’d encounter a system like this. Eight suggested that it might be used for psychotherapy or other support. Many were concerned about their privacy (5) or data (7).

Perhaps most importantly, “participants were hardly aware that such assessments may happen without their awareness." One didn’t think that it was possible to assess personality in this way, and six expressed general discomfort about these systems.

Reflections and thoughts

I keep connecting this paper to adversarial machine learning in my head, in which one attempts to fool a model through “adversarial” (malicious, invalid, or tainted input). This work makes the users the adversary, which I find extremely cool.

Putting users at the center forces us to confront important questions about people’s mental models of these systems. The extent to which people are able to trick a personality assessment chatbot will likely depend on how much they know about how it works.

On the whole, participants were not very successful at tricking the chatbot. The authors believe one reason to be that participants were only able to vary a couple of things at once—while they could try to e.g., be more friendly or use more swear words, the mental burden of changing their entire personality at once was too much.

Also, the chatbot did poorly

It’s also worth calling out that the chatbot in question didn’t even do a good job! It overpredicted extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, and underpredicted conscientiousness and openness. The authors call this “of secondary interest,” since they were most interested in the changes participants were able to induce, and that’s fair; it matters, though, when thinking about the bigger picture.

Someone wishing to trick a flawed personality assessment chatbot needs more than a mental model of how automatic personality assessment works. They also need to develop a model of how and why they might be flawed, and how to exploit these flaws.

It’s also worth noting that many participants felt a moral obligation not to trick such systems. Furthermore, many were unfamiliar with the Big Five personality theory. In that case, how are you supposed to trick a chatbot trying to infer traits you’ve never heard of?

Implications for education

The authors note that participants underestimated “the depth and possibilities of automatic personality assessment”—being surprised that these systems could be concealed and not knowing where they might be encountered. At the same time, they overestimated the accuracy of these systems—placing a lot of weight on the chatbot’s assessment of their personality.

This is an interesting dynamic; that people don’t necessarily know where these systems are, but where people do find such systems, they assume that they work well. This suggests the need for more general computing literacy education: how these systems work, where they are, what their uses are, what their limitations are, and more.

But perhaps this is too optimistic. “Our participants felt helpless against profiling algorithms and the companies behind them, with the consequence of giving up on their data and privacy,” the authors wrote (emphasis mine). Is this somewhere we need policy to help us? The authors think so, writing that “current legislative approaches are not sufficient”:

Furthermore, we call for transparency and understandable explanations about the data collection and analysis practices. When users are aware of it, they may be able to act prudently or turn away from it. As for other data, users should be granted access to their profile and be in control of its’ use at any time.

These are interesting questions about the interaction between people, technology, and society. What kinds of systems are we building? Who do they give power to? Who do we leave behind? This work is about so much more than personality chatbots—it’s getting at the heart of core questions in HCI.