What are members of Congress tweeting about, and how can we use machine learning to infer this? In this ICWSM 2020 paper, the researchers try out both supervised and unsupervised learning on all the tweets from members of the 115th Congress (Jan. 2017 - Jan. 2019).

Authors: Libby Hemphill, Angela M. Schöpke-Gonzalez (from University of Michigan)

Link: ICWSM Proceedings (open access), prerecorded talk

Summary and contributions

Knowing what politicians are talking about helps to create an informed constituency. As more politicians use social media, knowing what politicians are talking about on social media is still helpful, and can now (as this paper shows) be automated.

This work contributes two models for labeling topics in political social media content, one supervised and one supervised. They also discuss the costs and benefits of these approaches (and tradeoffs between them). And their code is open source!

Why Twitter? Existing work on political attention focuses on political speeches. But Twitter is being used more and more by politicians. And while it might not be representative of how the average American votes or thinks, it’s used by political elites (including the media!) to shape coverage and discourse.

Why automation? Two reasons:

- manual labeling is not efficient given how much members of Congress tweet

- topics change over time, and an unsupervised approach might fill in the gaps left by pre-defined codebooks

Datasets

Using the Twitter search API, the authors collected all tweets from official members of the 115th Congress (from January 2017 - January 2019). This was a dataset of 1.5M original tweets from 524 accounts.

Preprocessing: these steps were—

- stemming: not done, because the (mis)spelling of tweets is often semantically meaningful

- stop-words: removed in both English and Spanish. Words were tokenized with NLTK’s

tweetTokenizer. - tokenization: they stuck with unigrams, finding them more interpretable than bigrams and unigrams+bigrams.

In NLP terms, “documents” were individual tweets (rather than, e.g., all the tweets by someone in a day). This makes sense in the Twitter context; members of Congress will tweet about multiple unrelated topics per day.

When reading about NLP work, it seems like so much of the work is dependent on your preprocessing choices. I’m glad that the authors explained it in so much detail (and releasing the code is even better!), but it’s surprising to me that nearly a page was devoted to preprocessing.

Models

Both the supervised and unsupervised models label the probability that a tweet is about a particular topic (which are given in the supervised case, but inferred in the unsupervised ase).

The supervised classifier is trained on tweets from Russell’s past / analyses of Senators on Twitter. The labels are from the Comparative Agenda Project’s codebook.

They trained four models, using a 90/10 train/test split for each. These models were:

- a random guessing, baseline model

- a naive Bayes model

- a logistic regression

- an SVM

The unsupervised topic model: they used the MALLET LDA model, where LDA stands for Latent Dirichlet Allocation. They found that using 50 topics (searching between 5 and 70) produced “the most interpretable, relevant, and distinct results.”

Along the way, they tried LDA in Gensim (finding it too hard to interpret) and Moody’s lda2vec (finding it took too long).

Evaluation: their primary evaluation for the supervised model was through an F1 score. The logistic regression achieved a score of 0.79, and other models performed worse.

Their evaluation for the unsupervised model is more interesting. They had two experts manually label topics then resolve disagreements. Quantitatively, they used the NPMI topic coherence measure (what?) to assess these.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of the unsupervised model is the ability to label non-policy tweets (which are out of scope for the CAP codebook). These topics include sports, holidays, sympathy, emergency response, or constituent relations.

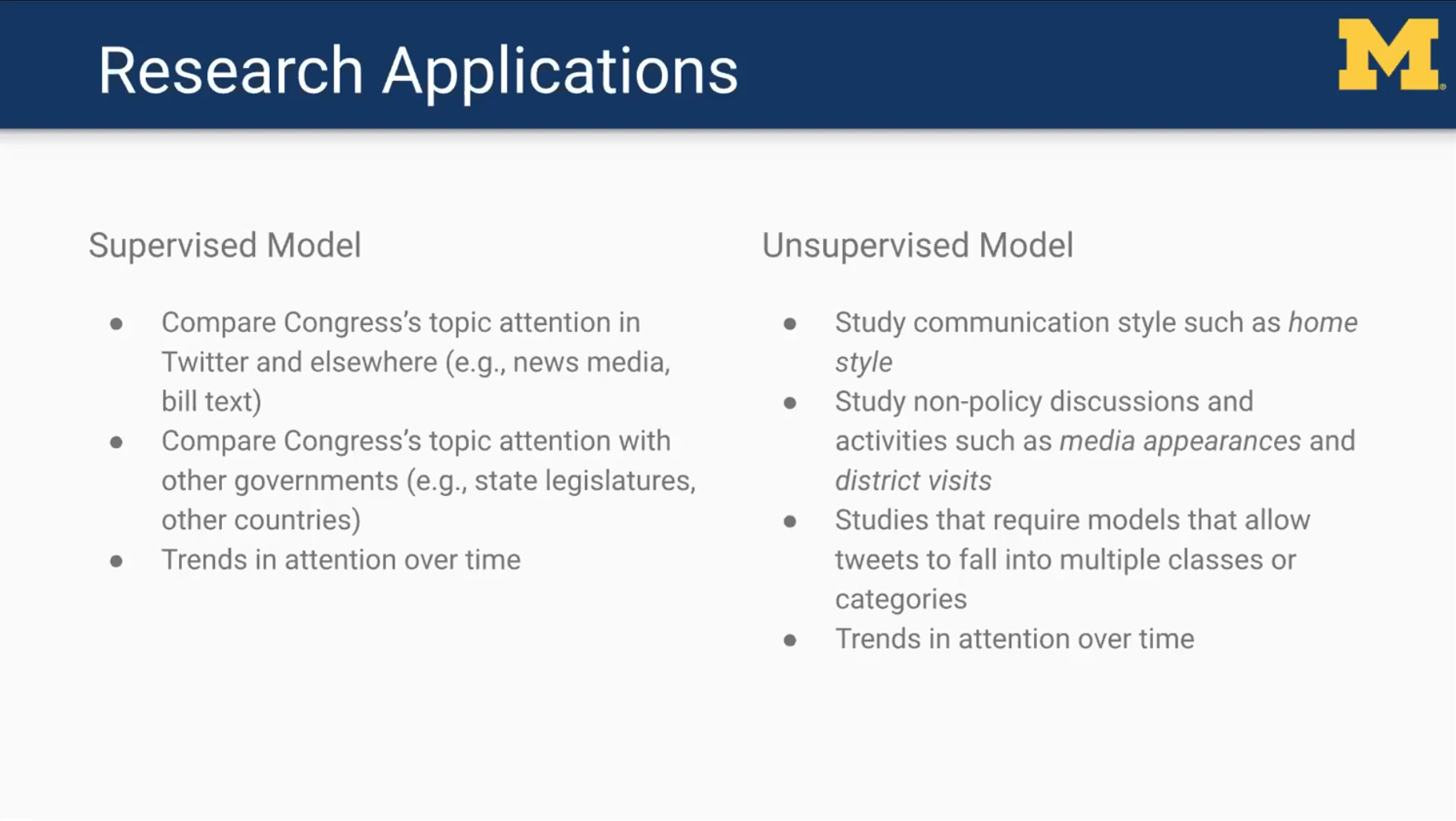

Research applications

I’m taking this slide the authors’ talk because it’s excellent:

One of the reasons I like ICWSM is because its submissions are often more practical than at other conferences. This slide is a great example.

The whole question about “how could this be used” is interesting because the timescale for how this could be use is so immediate. It doesn’t sound like that much more work to deploy this in the wild, but that could be useful in the leadup to the election in November!

Other thoughts

To me, this paper is a good example of how so much research is an example of asking (and properly framing) the right question. “Hey, can we use topic modeling on tweets by members of Congress?” sounds like such a simple question, and none of the models they use are anything special.

Still, though, the combination of the question and results are clearly interesting enough to be published. (This isn’t a criticism of the paper—I just think the interesting parts are the questions, applications, and implications for future design, not the methods or results.)

On that note, I wish the authors had discussed more real-world implications for how this might be used. Would it be feasible for Twitter to label politicians’ tweets based on models like this? Would it be possible to create a search engine for members’ of Congress tweets about healthcare, social justice, or immigration?

Less importantly, I wish the authors had validated their unsupervised learning approach against some other kind of baseline. I’ve had issues running and tuning LDA in the past, and I would have liked to see its utility compared to, say, a tweet clustering algorithm, or some kind of simple keyword matching.

(Smaller questions: I wonder how these results apply to other countries. I wonder how these results apply to the current US Congress. I wonder how the ways in which Senators use Twitter changes during their 6 year tenure, i.e., closer or further from re-election.)

The “politicians on social media” space is interesting, though, and I think there’s more work to be done here. Perhaps most importantly, this kind of paper makes me feel like I could do this research, too.