This CHI 2020 paper studies what happens if you push the limits of personalized ads by using data that people didn’t realize they’d given out.

Authors: Julia Hanson, Miranda Wei, Sophie Veys, Matthew Kugler, Lior Strahilevitz, Blase Ur

Link: ACM Digital Library

I realized that I was burning out by trying to read a paper a day, so I took a break for a few days to work on my side project and play some Animal Crossing. Both were fun uses of time, but something I’m working on is being able to do less of more things … instead of spending the entire evening working on my project or playing AC, being able to spend a couple hours on each and an hour to read a paper. It’s a work in progress.

Background

Modern advertising is often personalized; sometimes this is from cookies that follow you around the web, and other times it’s from email lists or behavior-based ads on Hulu or YouTube. These are gradually getting more and more personalized. The authors use the term “hyper-personalization” to refer to ads that make use of deeply personal characteristics—i.e., not just age and gender, or even basic interests, but (to use a famous example) whether or not they are pregnant.

The authors here were particularly interested in the misuse of information: if you collect data in one context, how do people feel about it being (mis)used for advertising?

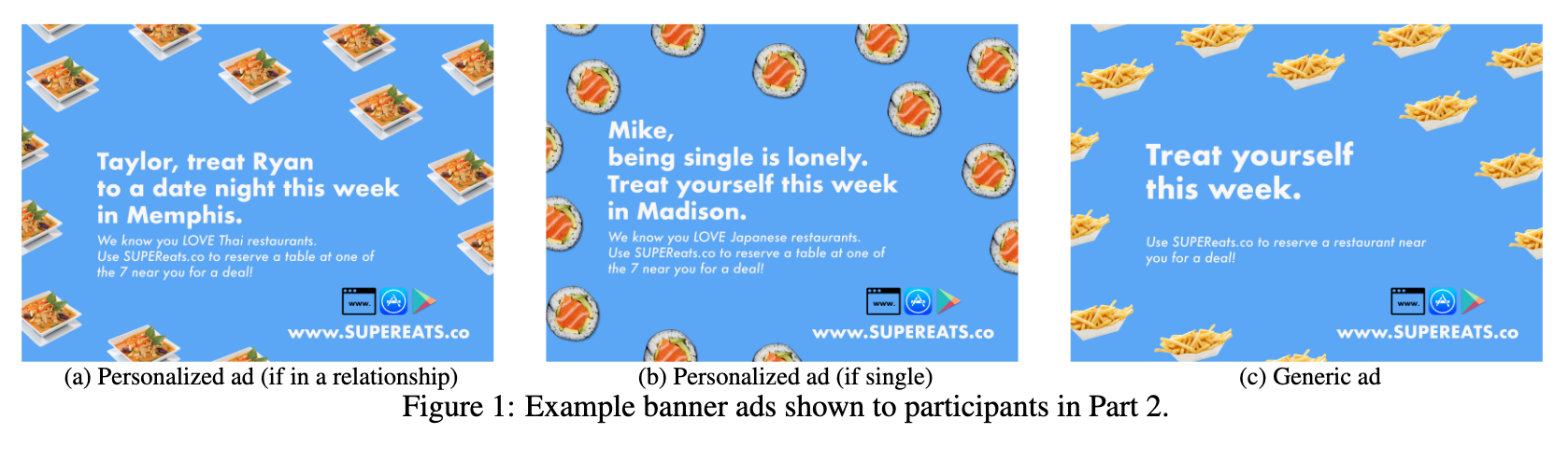

We surreptitiously collected participants’ first names, their romantic partners’ names (or that they were single), their preferred type of cuisine, and their town-level location. We randomly assigned some participants to receive an ad with this information, either as a typical online banner ad embedded in our survey software or as a robotext sent to their mobile phone from a short-code number. … We hypothesized participants would be less likely to accurately reveal personal information if they had received a hyper-personalized ad, as opposed to a generic ad. We expected personalized ads would cause feelings of privacy invasion, and that those feelings would lead participants to choose “prefer not to say” to stop the spread of their personal information.

Let’s dig in.

Methods

This was “a two-part deception study.”

In the pre-study, the authors used Mechanical Turk to gather a list of invasive questions (having been unable to find a metric for what makes a question invasive). They presented questions and asked users “if given the opportunity, I would choose not to answer this question.” This resulted in 43 invasive questions.

The main study had two parts. The first was an online survey collecting personal information (and mood, using PANAS) amidst a barrage of distractor questions. The second part had six conditions: in-person, online with a robotext ad, and online with a banner ad, each split into a personalized ad and a generic ad.

The personalized ads were super creepy! And yet I’m sure someone with enough data on me could figure out where I like to eat or what my partner’s name is.

In the second part, participants received the ad (via banner or robotext), answered some questions about their relationship with technology, and then the invasive questions. (The responses were deleted via some custom JS in the Qualtrics survey software, so the authors only saw whether participants responded or chose “prefer not to say”—great ethical study design!) They were debriefed after this.

Interestingly, the study had two rounds! The authors first had their university’s affiliation in the disclosure form and study URL, but upon recognizing that participants used the University label as a reason to trust the study (and disclose their personal information), they redid the study under the “Institute for Interests and Demographic Research.”

Results

Deception effectiveness: first off, most participants reported seeing the ad, which is good. Most who saw it did not suspect that it was part of the study. 13% of the robotext participants only started to suspect the text was study-related when the questions got more invasive or started asking about advertising.

Reactions to the ad: 53% of the personalized banner ad group and 44% of the personalized robotext groups volunteered (via free response text) feeling some combination of scared, shocked, creeped out, or otherwise uncomfortable. Some explicitly said that they “felt like my privacy was being invaded and that companies were using leaked information.” The generic ad groups were indifferent or confused about why a survey had an ad.

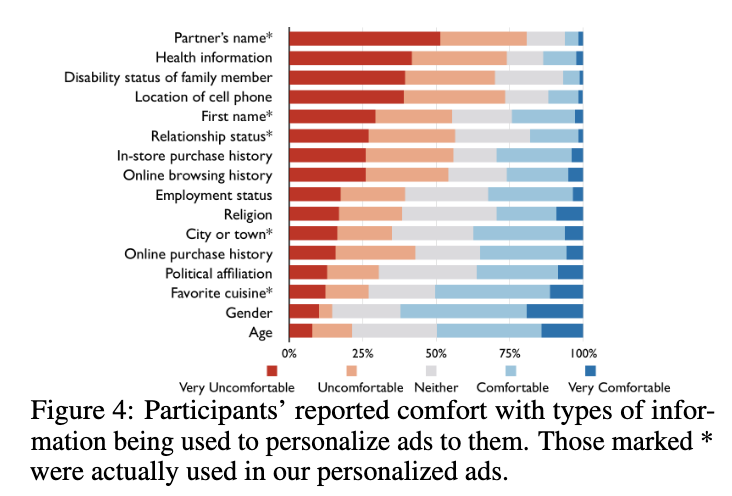

Comfort with information: this figure shows reported comfort with different types of information, and it makes intuitive sense. By far, people were most uncomfortable with use of their partner’s name, health information, or disability status of a family member; and more comfortable with age, gender, or favorite cuisine.

Information disclosure: this is the most surprising part of the results.

Despite their negative reactions, participants who received personalized ads did not differ significantly from those who received generic ads in how many questions they answered.

Why did participants (in any group) choose to answer the invasive questions? A combination of reasons:

- trusting Prolific and/or Qualtrics (the survey software used)

- assuming that the study had been vetted by Prolific (it hadn’t)

- needing money, so they indiscriminately completed any study (“if I wasn’t flat broke I wouldn’t be doing this”)

- not considering or caring about how IIDR (the fictional institution) would use the data

Discussion

The main reason I’m glad I read this paper is because it feels like a great lesson in ethical survey design. Deliberately studying people’s responses to invasive advertising and questions is, as evidenced here, useful behavioral research. It’s also dangerous, and I appreciate how thoroughly the authors discuss these tensions throughout the paper. They took great care to ensure the study was conducted ethically.

The results are interesting too, of course. The disconnect between feeling creeped out when advertisers use personal information and volunteering this information to a fake-but-legitimate-sounding institution is shocking. This is an example of the “privacy paradox,” in which “individuals report highly valuing their privacy, yet fail to take privacy-protective actions.”

Crowdwork is a particularly interesting case here—people doing crowdwork are often doing it to earn extra money, so they have an economic incentive to try to complete studies and volunteer information for that purpose (though that wasn’t the case here). This, combined with the lack of protection for crowdworkers, creates risk for them.

The authors suggest compartmentalization as a possible explanation:

Participants potentially compartmentalizing the privacy violation might further explain the absence of significant differences in disclosure across conditions. Many participants did not attribute the source of the hyper-personalized ad’s information to our Part 1 survey, so they may have considered the ad’s privacy invasion unrelated to the Part 2 survey.

That’s totally plausible—and a related finding was that participants sometimes blamed Google, Facebook, or various apps for this. (Perhaps unreasonably so, but maybe not—Google has the ability to know my partner’s name or the restaurant where we get weekly margaritas). That participants couldn’t identify the source of data leakage is troubling, but another instance of the privacy paradox.

One participant described giving up their personal data as a precondition for using the internet:

The internet and various apps require me to sign away some of my privacy in order to use them, and this includes personal information that I don’t want advertisers to see. I don’t want this personal, private information in a database. I don’t want the government or major corporations to know so much about me. They know more about me than I do at this point.

And the paper’s final paragraph is great, so I will simply reproduce it here:

In the current data economy, people are encouraged to give up vast amounts of personal information. Given the ubiquity of downstream transfers of personal information between nameless third parties, as a recent newspaper article about secret consumer scores emphasized [21], and the corresponding breaches of contextual integrity, the kind of depressed acceptance expressed by the above participant should not be surprising. Consumers’ autonomy is sharply limited when they do not, and cannot, know why their data is being collected, by whom, and for what purpose. Though sometimes outraged, they are unable to attribute privacy violations to their initial source and are unsure of where to direct their anger. In light of this, we should be slow to interpret the disconnect between individuals’ actions and beliefs — their privacy surrender — as the result of willing privacy calculus, with people freely choosing disclosure. Instead, we should recognize that the framework created by technology and advertising companies leaves upset consumers without a viable way of protecting themselves and productively expressing their disquiet.