How can we estimate suicides in real time when official data sources can have data lags of over a year? This paper, by researchers from Georgia Tech, the CDC, and the National Suicide Prevention Hotline, uses machine learning to model and forecast weekly suicide fatalities in the United States.

I saw this just-published paper on Twitter, and it caught my attention immediately. It was easy to approach and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. As a warning, this paper write-up discusses suicide.

Authors: Daejin Choi, Steven A. Sumner, Kristin M. Holland, John Draper, Sean Murphy, Daniel A. Bowen, Marissa Zwald, Jing Wang, Royal Law, Jordan Taylor, Chaitanya Konjeti, Munmun De Choudhury

Link: full text and PDF available online.

Background and motivation

From the paper’s importance statement:

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the US. However, official national statistics on suicide rates are delayed by 1 to 2 years, hampering evidence-based public health planning and decision-making.

This long of a delay is challenging for public health. Decision- and policy-makers cannot accurately plan targeted interventions, or even budget appropriately, when looking at data from a year back.

As a particularly compelling example, consider the present situation of COVID raging in the United States. If we had estimates of suicide fatalities over the past few months, one could imagine the impending relief bill allocating funds to interventions and prevention programs. (Partisan politics, and the question of whether the model holds up in COVID-times, notwithstanding.) As it stands, though, it doesn’t seem like we have much information on how suicides have changed during the pandemic.

Social media holds a lot of promise in this space; it’s one of the richest sources of real-time data available. But blindly using social media data is a minefield:

Moreover, methods that use social media data alone can be limited by issues of proxy and sampling bias, a lack of demographic and geographic representativeness with respect to the general population, structural idiosyncrasies owing to different platforms’ distinct affordances, and epistemological issues around what social media–derived signals really mean when taken out of context.

This work combines varied data sources and considerable domain expertise to estimate weekly suicide fatalities.

Data sources and methods

The authors describe the data they used.

Admin data from health services:

- the proportion of ER visits for suicide

- the volume of calls to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- the proportion calls to US poison control centers attributed to intentional self-harm.

Online data:

- from Google Trends and YouTube Trends, search interest in suicide-related terms

- from Twitter and Tumblr, the volume (or proportion) of suicide-related terms, hashtags, or phrases

- from Reddit, participation in suicide- or mental health-related communities

The authors looked into economic data from the Federal Reserve (unemployment, consumer price index, etc.). They also considered the number of daylight hours (at the center of the US, because this model is not geo-specific).

These (along with Tumblr data) didn’t end up being used in the final pipeline. Including them degraded the model performance. That’s how machine learning goes!

The machine learning pipeline consists of two steps. First, predict (through linear regression, random forests, and support vector machines) suicide fatalities on each individual data source. Second, a neural net uses the individual model outputs to produce a final estimate.

I hadn’t heard of this kind of ensemble method before, but it makes a lot of sense to me! This reminds me of (one way) how the CDC does flu forecasting, through taking many noisy estimates and aggregating them.

It also doesn’t look like the authors used specialized time series methods. Instead, they construct features over time windows and use those as inputs to garden variety machine learning.

Evaluation and implications

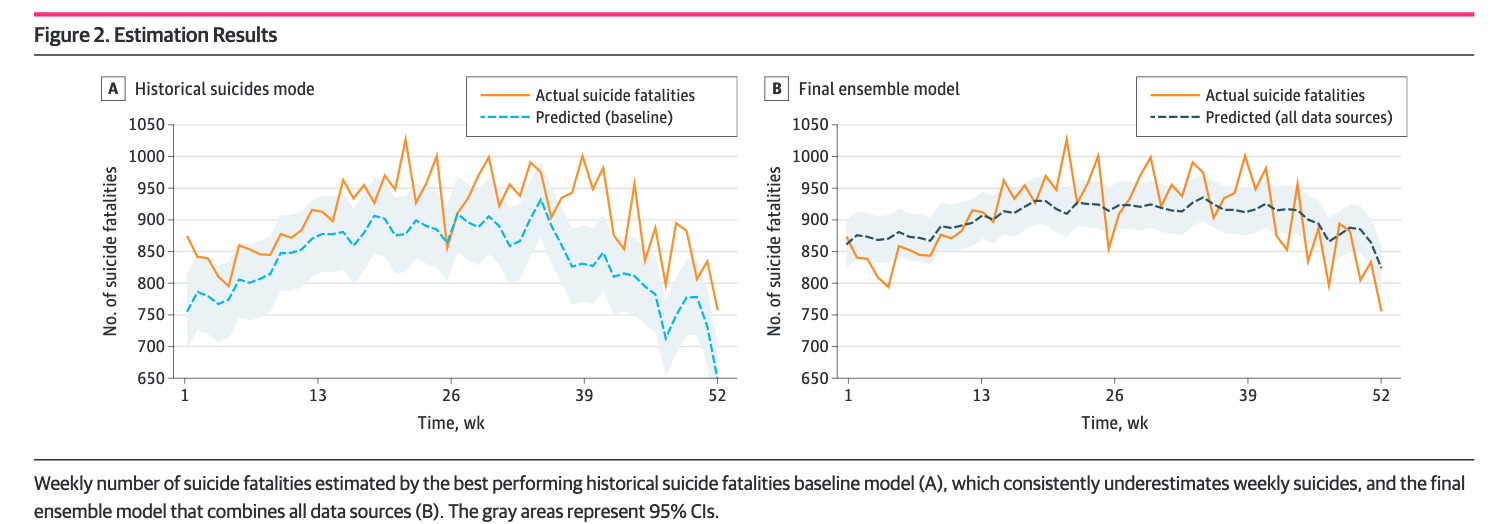

The model was trained on data from 2015 and before; validated on data from 2016; and tested and reported on held-out data from 2017. The largest correlation between an individual predictor and actual suicide fatalities is the historical data; this means that seasonal variation is strong, and we can use historical data as a prediction baseline.

We see that the baseline underestimated an increase in suicides in 2017; the model doesn’t. (Also—ouch—seeing 1000 people take their life each week really hurts. This graph is such a grim reminder of the people and lives behind the numbers.)

The implications are interesting. I don’t know a lot about public health, so I’ll refrain from writing too much, but the authors seem optimistic that this is (1) robust enough to be accurate in the future and (2) useful enough for real-world deployment.

For example, more timely information about rapidly increasing suicide trends could enable governmental funding and support for programs to prevent suicide in a way that better keeps pace with the growing magnitude of the problem. Such efforts might include more rapidly addressing clinician shortages in mental health care; expanding crisis intervention programs, such as hotline, chat, or text services; or strengthening policies and programs that address underlying risk factors, such as economic or housing instability.

My thoughts

What a great paper!

I love social computing work. I know that it’s easy to misapply social media data; think about all the ways that ‘machine learning model that predicts suicide’ could go badly! Here, though, we see the importance of having domain expertise—in this case, the CDC and National Suicide Prevention Lifeline—as collaborators for this high-stakes work. The paper speaks to both the immediate applicability and limitations of this kind of estimation.

One of my favorite papers in this space is Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: a critical review, by Stevie Chancellor and Munmun De Choudhury. So much work on mental health and social media doesn’t actually involve domain experts or medical professionals, and it’s dangerous.

I’m really interested in the practical deployment of a model like this. How often would it need to be retrained? How much will changes in popularity in Twitter and Reddit affect the model? What about new hashtags or suicide-related terms that emerge? For a ML model to be useful in near real time, maintenance is essential.

This is also the advantage of using an ensemble over a variety of data sources. Yes, the neural net weights would have to be retrained; but the model architecture is flexible if another useful data stream arises. No single data source (besides perhaps historical data) is crucial.

Finally, this work used data from 2014 to 2017. The natural, timely question is the extent to which COVID will affect both suicides and model estimates. On one hand, the pandemic is unlike anything we’ve ever seen before; if there’s anything to break a model, it’s this. On the other, the data sources might be varied enough to capture the actual underlying factors here.

This work advances the very first efforts in achieving a near real-time understanding of suicide in the United States.

That’s great to see.