Continuing my series on building a tool for Pokemon Mystery Dungeon, this post describes my experiences trying, failing, and trying again to build a web app.

Recap: cracking passwords

The goal of this project was to build a tool to help players with the newest Pokemon Mystery Dungeon game. I want my tool to (1) rescue players who fainted in dungeons and (2) generate synthetic rescue missions that players can go on.

In the last post, I described my attempts to re-implement the logic used in the game. That was unsucessful, but someone more skilled than me did it instead. Since copying someone else’s implementation was boring, my project turned into “let’s build a (better) web app for this.”

My front-end experience

I don’t have much front-end experience; more than the average data scientist, but less than the average software engineer. It’s not like I need it day-to-day; I’d be able to get by without knowing any JavaScript at all. At the same time, I can’t deny that having a basic understanding of web tools and front-end skills has helped me.

Most of this came from when I was a software engineering intern at Qualtrics working on some of their Angular (or AngularJS? I don’t remember the difference.) dashboards. The internship was a great experience, but I didn’t particularly enjoy the work—which is how I landed in data science a year later!

I’ve also learned a fair amount of JS from building a handful of Chrome extensions for automating or improving / common / tasks, and also from throwing together a Flask app at work for an interactive demo of a tool I built.

So why do I keep coming back to front end projects? Why not spend my time on something more immediately applicable to data science? The idealistic answer is that learning new tools and improving my general knowledge of software is always a good thing. The practical one is that this is a fun project, and the best project is one that I’ll actually do.

It’s this attitude—that learning is itself a worthy goal—which keeps me coming back to something that I’m simply not very good at. But then again, how else do you learn?

Let’s dive in.

Attempt #1: build off someone else’s work

Me, probably: Hey, can I borrow your UI?

Someone who knows what they’re doing: Sure, just change it a little so that it doesn’t look copied.

I’ve mentioned a couple times how I’ve been playing a ton of Animal Crossing lately; one of the tools that helps me do this is a site called Turnip Prophet. It’s a minimalist single-page app that attempts to predict your “turnip prices” for the week. (If you don’t play AC, imagine predicting stock prices if we were able to datamine the Dow Jones.)

The UI inspired me: it was simple, it was open-source, it didn’t have a backend, and it seemed like something I could do. And so I cloned the repo and gradually started changing things to get closer to my vision.

And … I did! It took a few days and lots of trial and error, but I transformed that app’s UI into my own. Some of the JS still needed work—there were lots of placeholders for things I’d need to do later—but it at least looked passable and the elements were responsive.

There’s a “but” coming, right?

When everything falls apart

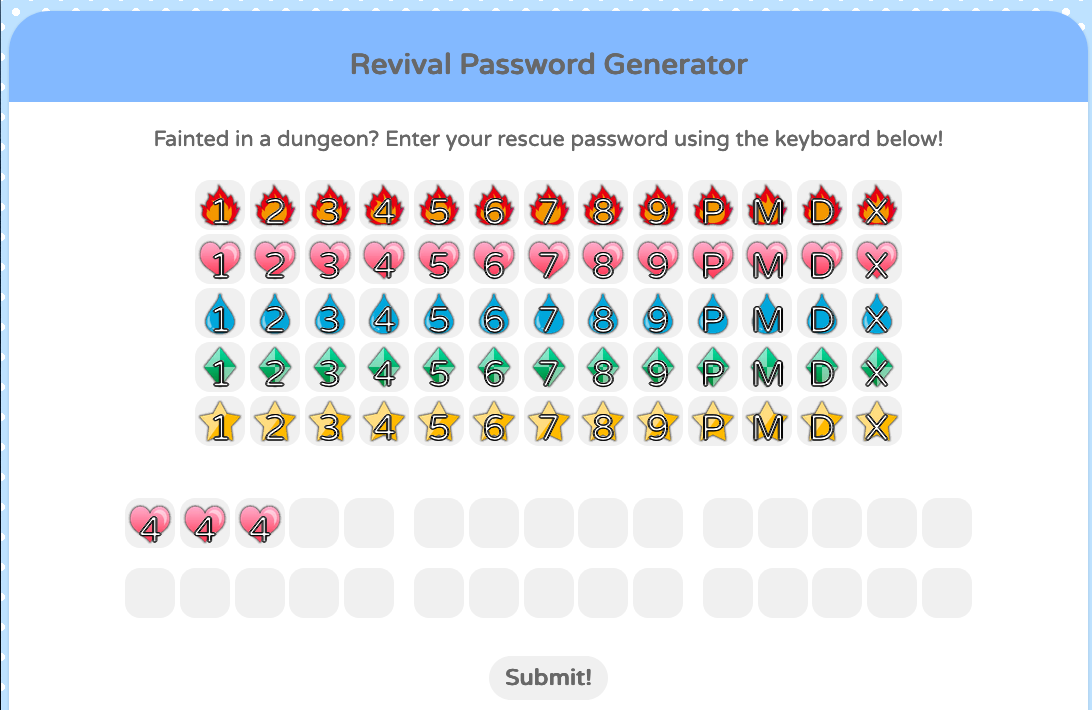

That was part 1—building the part to enter a rescue password and get a revival password back. Everything either already worked or was in a place where I knew I could get it to work (i.e,. no unknown unknowns).

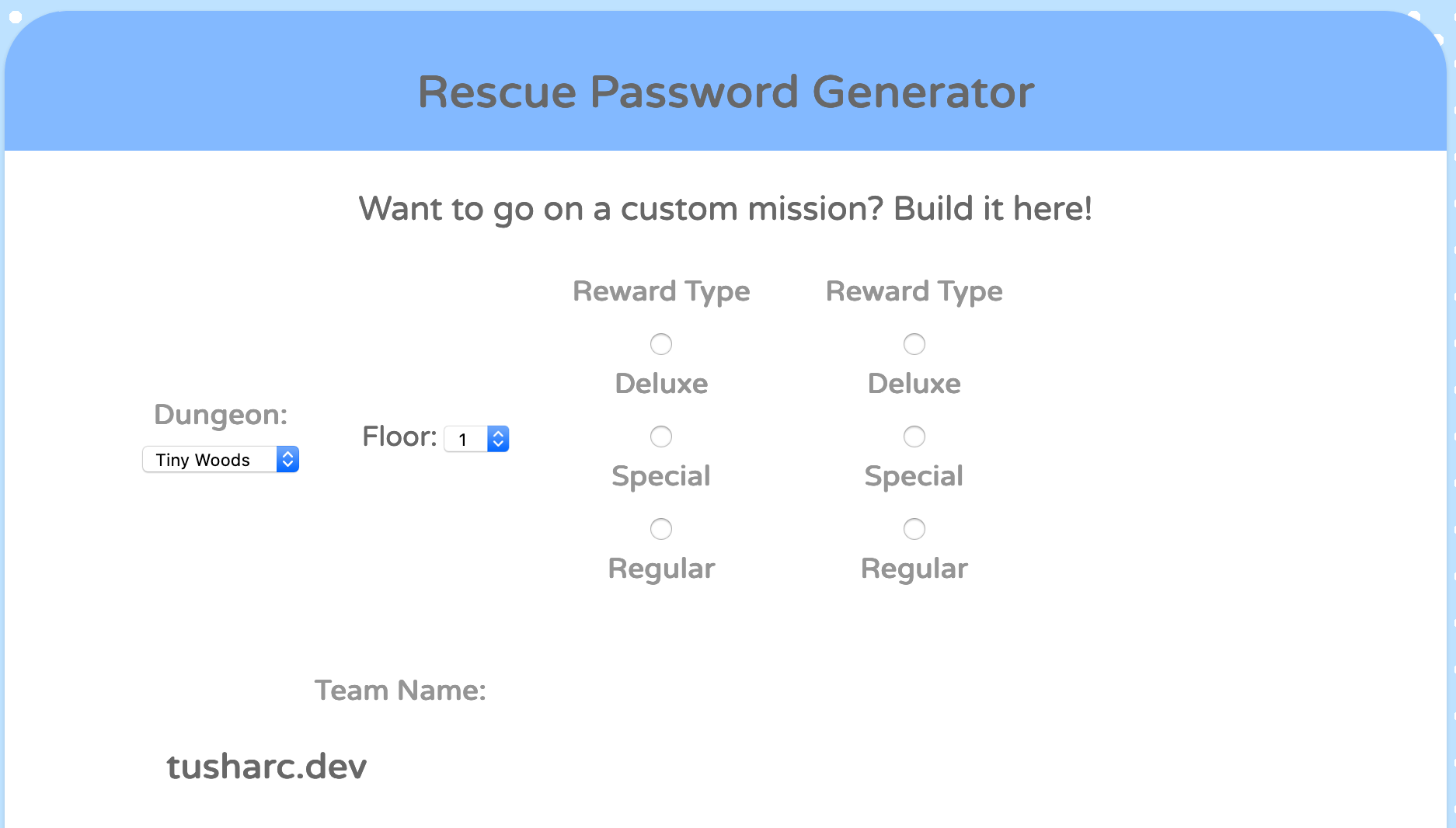

Part 2 was harder: let a user choose a dungeon, floor, team name, etc., and generate a synthetic rescue code for them. There were more ways users had to interact with this part of the app, so naturally it was trickier to get the UI right. Instead of exclusively having the symbols above and a “Submit!” button, I now had dropdowns, radio buttons, text inputs, explanatory text, and more.

I started floundering: I tried repurposing some of the UI components that the Turnip Prophet creator had built, but this didn’t work.

Figuring out how to get everything to line up properly was challenging. I’m sure that I could have done it, given enough time, but this just didn’t appeal to me. Around the same time, I started reading lots of CHI 2020 papers, which took up most of my free time, so this sputtered for a week or two.

Enter: Tailwind CSS

Some time later, I was on Twitter, and Brett Cannon, a Python core developer who I follow, asked:

If I were to start a new project that was going to require some (mobile) web UI, what CSS frameworks are people using these days? (E.g. Bootstrap, not React)

An overwhelmingly common answer in the comments was Tailwind CSS, which claims to be a “utility-first” CSS framework. The idea is that Tailwind gives you the building blocks of customization, and you combine them together with what looks suspiciously like inline styles.

Why is this better than inline styles? I asked. I wasn’t alone: the documentation answers this by saying that Tailwind helps you design visually consistent styles, that it makes it easier to build responsive UIs, and that maintaining this is far easier than maintaining CSS.

My next step was to ask my React-developer roommate, who gave me more context into why anyone would want this sort of thing. He pointed me to the State of CSS Survey, which showed that Tailwind had a remarkable 81% satisfaction (with a small userbase).

CSS flashbacks

It’s worth noting that my experiences with CSS have … not been positive. They can be lumped into two groups: trying to write CSS from scratch myself, or taking a CSS file that someone else had written and making modifications for my application.

The first was simply painful; I often didn’t know where to start, and it felt like it took a ton of work to get a passable layout that didn’t look immediately awful.

The second was easier, and it’s what I did with both versions of my website, which first used sakura.css directly in the repo and later moved to Hugo. I stripped both stylesheets of things that I didn’t need. Making modifications was harder, though; I’d often not know what to change, or make changes and not see them reflected in my site.

One of the fears that I had deeply internalized about CSS was that it was unpredictable. Yeah, it’s a deterministic system, but to me it felt hopelessly complicated. I’d change a style on some selector, hoping for my button to turn blue or something, and … nothing would happen. Or (and I’m not sure which is worse), all my buttons would turn blue. Or an unrelated element would turn green!

Overcoming this has required changing my debugging attitude. I’m working on it, but I can’t say I’m fully there yet; CSS still feels so hard for me to understand.

Overcoming NPM

I also realized that I had an aversion to anything that I had to NPM install. I was so prepared to use Tailwind from a CDN or just include the source myself, but then I realized this was a terrible idea due to (1) node_modules and (2) Tailwind’s own recommendation.

So there I went—installing Node and NPM, installing Tailwind and the related packages into the project directory, creating package.json with the recommended build script, installing live-server to autoreload my page on changes, and … starting my new UI from scratch.

This was a surprisingly positive experience. For as much as /r/programming likes to shit on NPM and the JavaScript ecosystem, I had no trouble setting this up. Doing a comparably complex task in Python, my favorite and most proficient language, would have probably been harder because of how fragmented their packaging ecosystem is.

Three hours with Tailwind

My experience with Tailwind has so far been exceptionally positive. The documentation is excellent, and the examples from their video tutorials are well-motivated and easy to follow.

Additionally, the video tutorials reset my mental model for how hard making interactive, responsive UIs is. Making the main container adjust to different widths is fine and all, but the videos helped me to see that thoughtful positioning of UI elements is different at different screen sizes. This is hard to do well, and I’d previously just brushed aside that complexity!

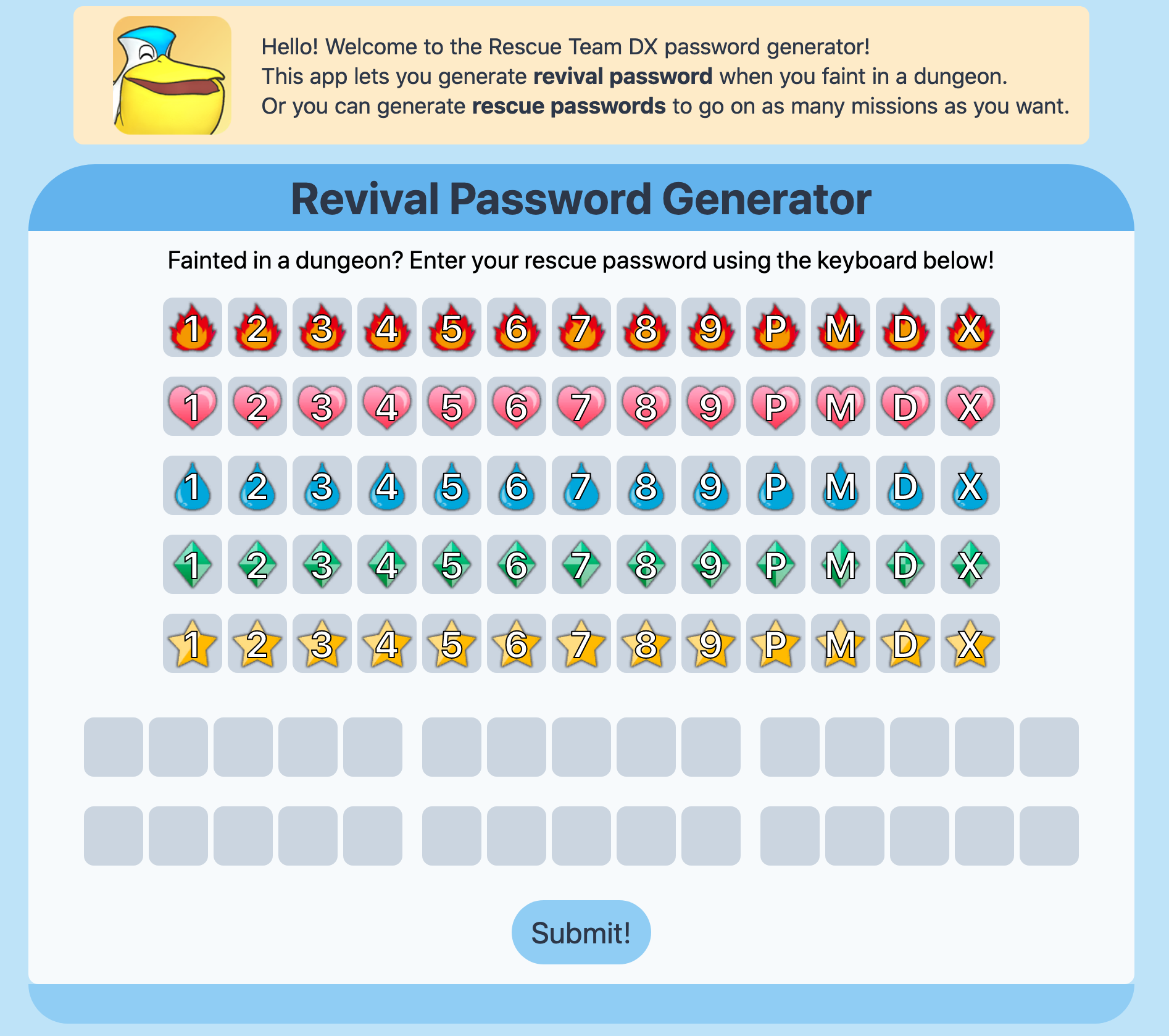

Using Tailwind, I was able to rebuild my UI in three hours during which I was only half-concentrating.

The details aren’t all the same, but that’s fine—those can be changed. The colors match reasonably well, and they could probably be improved with the help of a non-colorblind friend. Nothing is interactive yet, but that’s just JS I’ve already written.

The inline classes approach is stunningly simple. To make a button blue, I add the bg-blue-900 class directly to the HTML element, or bg-blue-400 for slightly less blue. There are nine shades of blue that I can choose from, and while I can add more if I really need to, Tailwind restricting my choices allows me to focus on the parts that matter (the layout).

One thing worth keeping in mind is that Tailwind forces you to always think in terms of CSS. In most places, Tailwind classes are shorthands for single CSS attributes, and it rarely introduces new abstractions like other CSS frameworks do.

I find this a positive: I don’t like abstractions for things that I don’t understand in the first place, so by writing in Tailwind I feel like I’m also getting better at CSS. Others who have higher-level needs might disagree.

Pyodide?

This post didn’t talk about Pyodide at all, which I was hoping would play a central role in this project. It looks like it won’t be doing much—using Python for layouts and UI work is out of scope here, and I don’t expect Pyodide to be much more than an interface between a garden variety web app and some black-box library code.

But I haven’t used it for anything besides a “Hello, world!” yet, so its entry into this project is coming up. I’m looking forward to its help with hooking up JS and Python.

So what is next, then?

The next steps are continuing to build out this UI. After that, I have to bring back the interactivity that I left in the old layout, refactor some Python code to have clear entrypoints, and then bring in Pyodide to hook up the JS and Python pieces.

I have a lot of open questions, like “how do I deploy this on Github Pages?” and “how do I design the second part of the app?” and “will this even work?", but I’m excited to tackle them.

That’s the best part about this project: that it’s so personal and interesting to me that I’m always happy to be working on it. I think that’s the best that any personal project can be.