Part 4 of the book Network Propaganda is titled “Can Democracy Survive the Internet?", and it focuses on how polarization came to be, how the media ecosystem came to be the way that it is, and proposed interventions (most realistically, regulating political advertising).

(I’m finally finishing this book. As a reminder, it’s available for free online!.)

Recap: the internet is not causing polarization

Let’s recap one of the main points from the first three parts of the book: if “the internet” is causing polarization and extremism, then we should expect to see rough symmetry between the left and right within the media ecosystem. This is not the case.

Instead, we see a mixed-media center-left that engages ~70% of the population, along with an increasing radicalization of the right ~30%. Moreover, the political science literature argues against the idea that the internet caused polarization. The left-and-center do not parallel the right.

These facts are as inconvenient to academics seeking a nonpartisan, neutral diagnosis of what is happening to us as they are to professional journalists who are institutionally committed to describe the game in a nonpartisan way. Both communities have tended to focus on technology, we believe, because if technology is something that happens to all of us, no partisan finger pointing is required. But the facts we observe do not lend themselves to a neutral, “both sides at fault” analysis.

I’ve said it before, and it applies here, too: technology isn’t neutral. Media isn’t neutral. There are no neutral explanations for what is happening to society, which is a function of deeply rooted power structures and shifts therein.

[Ch. 10] Polarization in American Politics

The authors write:

This chapter reviews the political science literature on polarization, showing that polarization in American politics long precedes the internet and results primarily from asymmetric political-elite-driven dynamics.

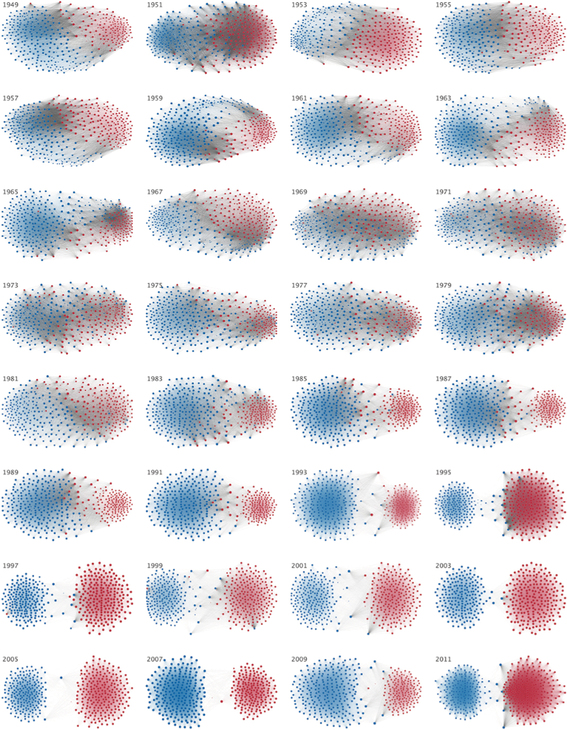

They present this graphic of partisanship in voting patterns for the US House from 1949 to 2011, which shows that while polarization is stark right now, it’s been steadily increasing since long before the internet.

This was largely due to party dynamics surrounding the New Deal and, later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The former, the authors note, relied on compromise between Northern Democrats and Southern Democrats (who didn’t want to undermine Jim Crow), and as these dynamics eroded as part of realignment following 1964, polarization increased.

The above is polarization among elites; there is less consensus about whether the public is polarized. (Congress being more polarized could be due to the public voting in more extreme candidates, or due to there being fewer moderate candidates.)

How much does this affect the large part of the population that doesn’t pay regular attention to politics? (What a privilege.) “A large majority of Americans do not have consistent and reliable ideological beliefs,” the authors write, a finding that has been replicated many times. Self-reported ideology does not predict opinions on many topic (immigration, gun control, foreign policy, and more); and they only predict abortion and LGBTQ rights when not controlling for religion.

The chapter concludes with a discussion about voter theory, including how people make voting decisions, develop policy preferences, and feel negatively towards the other party. The authors discuss a recent development, “negative partisanship,” which describes when voters have more hostility to the opposite party than they do affinity to their own.

This describes me. I have a deep disdain for the Republican Party for all of the obvious reasons right now. But I also don’t particularly care for the Democratic Party. I vote for them out of necessity in a two-party system, but I think their clinging onto the establishment (and some policy choices, but whatever) harms both them and the country.

[Ch. 11] The Origins of Asymmetry

This chapter describes how the right-wing media ecosystem—at which Fox News is at the center—came to be so prominent, rather than disappearing into a small niche (as happened to other right-wing media after WWII).

In 2016, Fox News was viewed more than MSNBC and CNN, and perhaps most important is that only 9% of Clinton voters used MSNBC as their primary news source, but 40% of Trump voters used Fox News for that purpose. Right-wing talk radio captured tens of millions of listeners, but left-wing radio was nonexistent. While there were attempts to create left-wing media that mirrored the right, they failed.

The chapter continues with a fair amount of media history that I will not summarize here, but is still interesting. At this point, I’m mostly trying to finish this book—sometimes “done” is the best feature. It goes on to make the point that Fox News really does occupy a unique place in the media ecosystem: 47% of “consistently conservative” respondents to a study used Fox as their main news source, but “consistently liberal” respondents were spread out across CNN, NPR, MSNBC, NYT, and more.

Additionally interesting is the question about trust in media; the General Social Survey collected information on those who have “hardly any” trust in the media, and this number is consistently increasing:

This is key:

Existing in a media ecosystem dominated by media whose role is to confirm your preconceptions and lead you to distrust any sources that might challenge your beliefs is a recipe for misinformation and susceptibility to disinformation. At the end of the day, if one side most trusts Fox News, Hannity, Limbaugh, and Beck, and the other side most trusts NPR, the BBC, PBS, and the New York Times, one cannot expect both sides to be equally informed or equally capable of telling truth from identity-confirming fiction.

The last part of the chapter is devoted to Facebook, where their own research scientists found that users sharing news did so in a polarized way “because they shared what their friends shared,” which segregated them into politically homogenous communities. (IOW, Facebook exonerated themselves from responsibility. eyeroll)

The data presented here provide evidence for the propaganda feedback loop of Chapter 3. “The positive feedbacks between the benefits to elites, who gain a reliable audience, the benefits to the broadcasters, who gain a loyal market segment, and the beliefs and attitudes of the population begin to reinforce each other within the feedback loop.”

Finally, the authors describe the results of three papers studying the “Fox News effect”:

- Stefano DellaVigna and Ethan Kaplan, “The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting,” 122(3) QJE 122 no. 3 (August 2007): 1187–1234.

- Gregory J. Martin and Ali Yurukoglu, Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization., NBER Working Paper, April 5, 2017.

- Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, “What drives media slant? Evidence from US daily newspapers,” Econometrica, 2010, 78 no. (1), (2010): 35–71.

And they leave us with the following conclusion:

Looking at the 2016 election, anyone assessing the impact of cable versus that of the internet has to contend with the fact that Trump supporters were, overall, primarily to be found in demographic groups that were the least attentive to online news sites and social media. … It is simply unreasonable to pin the blame for patterns of trust and distrust in media, or the rise of Trump, on a medium [the internet] that is consistently used less by demographic groups that express that distrust or support the president and is used more by populations that hold the opposite position on both questions. (p.340)

[Ch. 12] Can the Internet Survive Democracy?

This chapter discusses five failure modes of the internet that “limit the benefits of decentralized digitally-mediated collective action.” As the authors wrote this book, and still today, “the prevailing zeitgeist seems to be that all the promise of the internet has been swept away in a cloud of manipulation and abuse.” Ouch, but, fair.

1: the failure to convert a momentary surge of passion into a longer-term effort. Movements, given power because of the internet, die out because another takes over or because people lose interest. Platforms like Twitter and Facebook draw attention to what’s happening “now,” and just as quickly as a movement appears, it can fade away.

2: the failure to sustain decentralized openness into a more structured political organization. The authors give the example of how MyBarackObama.com, once a platform for people to organize decentralized meetups or bundle their own campaigns, was dismantled after the 2008 election—forcing Obama to build a new campaign machine in 2012! I wrote about this in A disaster in Iowa:

Instead of investing in sustainable platforms and funding them between cycles, the Democrats have chosen to lean on consultancies and one-off solutions. Instead of building out an actual technology organization, engineers and technologists are hired for short-term positions and laid off after the election.

Sustainable technology requires sustained investment, and this is a failure mode (not to be confused with a flaw) of the internet.

3: is the power of well-organized, centralized powers to move millions of people starting from the center, instead of the other way around. This failure mode describes how large powers (read: Google and Facebook) can manipulate the internet for their own use.

4:, then, is that the methods that help distributed networks to circumvent established institutions can also turn them into repressive mobs; see cancel culture for an example, or honestly Twitter as a whole. This doesn’t have to do with elections or policy, necessarily, but intimidation campaigns can be quite personal and dangerously harmful.

5: finally, is the susceptibility of the internet to disinformation and propaganda, which is what inspired this book. “The critical thing to understand is that the internet democratizes, if it does, only through its interaction with preexisting institutions and organizations—working with them and around them, and creating new alternatives that interact with them.”

Reflections

Instead of thinking about whether the internet democratizes or not, let’s think about who it in terms of power. Who does the internet give power to, and who does it take it away from? (Substitute “the internet” with any technology, and you get a similarly interesting question.)

In some ways, it creates a platform for historically marginalized voices, as we’re seeing now with #BlackLivesMatter. The internet has allowed videos of police brutality to be instantly viewed by millions of people. It can organize people together, through petitions, donation drives, “canceling”, and digital action, to create power where there previously was little.

But just as easily as these voices arise can they be suppressed, through oppressive algorithms, aggressive moderation, or all kinds of systems that perpetuate inequity. “The internet,” then, is not an entity; parts of it are good, parts of it are bad, and the vast majority sits squarely in the middle.

[Ch. 13] What Can Men Do Against Such Reckless Hate?

This is the final chapter, describing changes that might be made to combat the findings of the rest of the book. It warns that “broader systematic solutions are only likely to come with sustained political change.” Furthermore, any change will require an uncomfortable understanding of the partisan nature of the problem: there’s no neutrality when only one side has radicalized.

The chapter focuses on:

- a longer term, more fundamental solution of political-institutional change on the right

- a shorter term reorientation of how journalists work in an asymmetric media ecosystem

- practical solutions to technology-dependent problems (increased control of unacceptable content, regulation of advertising)

One of the clearest findings was the near disappearance of center-right media; the Wall Street Journal vaguely fills this role, but readers on the right don’t pay any more attention to it than readers on the left. Fox News became the leader of the right-wing media ecosystem, and some were noticing an “epistemic closure”; the following is from Julian Sanchez of the Libertarian Cato Institute:

Reality is defined by a multimedia array of interconnected and cross promoting conservative blogs, radio programs, magazines, and of course, Fox News. Whatever conflicts with that reality can be dismissed out of hand because it comes from the liberal media, and is therefore ipso facto not to be trusted. (How do you know they’re liberal? Well, they disagree with the conservative media!) This epistemic closure can be a source of solidarity and energy, but it also renders the conservative media ecosystem fragile.

Crazy. But that’s exactly what the authors assert has been happening. The question becomes how centrist Republicans, now being pulled in two directions, will respond; will they push the conservative media ecosystem back to reality?

“We are under no illusion that such a reorientation will be easy, and we are not even sure it is possible,” the authors write; they don’t even have advice for how to start this. But without this reorientation, it’s difficult to see anything changing.

Most Americans, however, are not part of this ecosystem. The crossover audience of conservative and independent viewers who watch CNN and read NYT can still be influenced by mainstream media. This is good—just not enough. The authors recommend that media recalibrate its commitment from one of neutrality to one of objectivity; that is, in an environment where the two sides are unequal, covering them “neutrally” is impossible.

The authors call for regulation of social media platforms (surprise!), but bring up the German NetzDG law as an example of how this can easily go wrong:

The [NetzDG] act applies to platforms with more than two million registered users in Germany … The law requires these larger platforms to provide an easily usable procedure by which users can complain that certain content is “unlawful” under a defined set of provisions in the German criminal code.

Criticisms center on the idea that it would force companies to over-censor content, rather than risk the harsh fines associated with it. This, incidentally, is precisely the attitude that created Section 230 in the United States.

Meanwhile, Germany’s past experience with Nazism led it to adopt a more aggressive intolerance of counter-democratic speech than, say, the US. This is another wrinkle in the calls for regulation: cultural norms are different across the world, and it’s unlikely that a California- or US-based law placing restrictions on Facebook would be sufficient for a global platform.

Online political advertising, meanwhile, is a more tractable problem. The authors discussed the Honest Ads Act, which was bipartisan legislation to reulgate political advertising (separating paid and unpaid communication, requiring disclaimers on digital ads much like TV, and requiring the creation of a fine-grained public database of “issue advertising”).

The bill requires the very biggest online platforms (with over 50 million unique monthly U.S. visitors) to report all ads placed by anyone who spends more than $500 a year on political advertising to be placed in an open, publicly accessible database. The data would include a copy of the ad, the audience targeted, the views, and the time of first and last display, as well as the name and contact information of the purchaser.

This data exists; the authors assert, and I agree, that making it publicly accessible is important for transparency of advertising. The rest of the chapter concludes by briefly discussing other ideas—fact checking the most prominent—but I’ll leave this post here.