On Tuesday morning, I came across CHI Nordic 2020, which was a mini-conference put together to present and discuss Nordic papers from CHI 2020. I joined the last session on “computational materials” and watched 3 talks.

Similar to how I watched a few talks from ACM FAT*, I wrote a couple paragraphs on what I learned from each of these. I found this a great way to engage with research that I probably would have ignored otherwise. Recordings are available on YouTube.

Brainsourcing: Crowdsourcing Recognition Tasks via Collaborative Brain-Computer Inferacing

Authors: Keith M. Davis, Lauri Kangassalo, Michiel Spapé, Tuukka Ruotsalo

ACM DL link: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3313831.3376288

The researchers motivate this work by talking about crowdsourcing, including macrowork (open source software, editing Wikipedia) and microwork (captchas or individual labeling tasks). Their goal is to determine the extent to which one can use brain signals as signals for a classifier. The P300 component of ERP data (??) is related to the idea of relevance, so they used that.

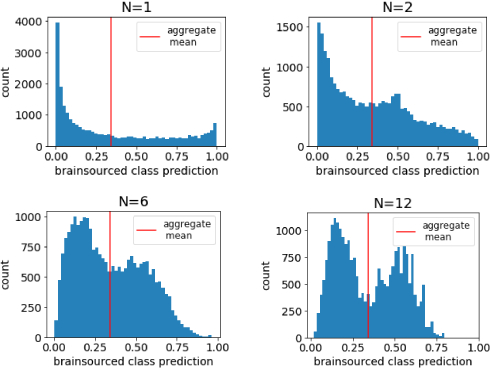

Participants hooked up to an EEG saw images of faces on a screen, with instructions to observe if the faces were smiling or not. A classifier is trained on the P300 signal from this EEG, and the classifiers from several participants are combined into an ensemble. The ensemble performs better than any individual, and as more signals were added, a clear bimodal distribution emerged.

This gives a whole new meaning to “human-computer interaction”! What an interesting work—discussion focused on details of the brain signals & the (un)ethical considerations of this kind of technique. One could imagine new labor paradigms that exploit people’s brainpower, subliminal probing to violate people’s private thoughts, or more, and that’s as interesting to think about as the work itself.

GRIDS: Interactive Layout Design with Integer Programming

Authors: Niraj Ramesh Dayama, Kashyap Todi, Taru Saarelainen, Antti Oulasvirta

ACM DL link: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3313831.3376553

The inspiration for this work is that grid-based layouts are commonly used to create user interfaces. In the proposed system, a designer will specify the kinds of elements that they want (header, footer, a paragraph, video with a caption, etc.), then this MILP system will generate candidate layouts. This builds upon other work in computational UI design. This kind of method provides guarantees about the output, e.g., that related items are grouped together, that the overall shape is rectangular, and that items are aligned on common axes.

They consider several key features for designers:

- “controllable diversity,” that this tool can generate multiple candidate layouts

- “autocompletion of partial designs,” that a designer might already have some idea for how they want certain elements to appear, so this tool can fill in the gaps

- “local search”, or being able to find candidates that are similar to a preexisting layout

- constrained designs, by locking certain elements in certain places (e.g., a header or image location)

The system was user tested on 16 professional designers on 3 design tasks. They found that it was reasonably easy to use and also that the optimization objective was a good match for the fuzzy “quality” of a design.

One interesting question asked if this could be extended for other types of design goals—Google, for example, might want to create a layout that makes an ad visible to a user. One of the authors responded that it might be possible using some kind of measure of how salient each layout element is.

Between Scripts and Applications: Computational Media for the Frontier of Nanoscience

Authors: Midas Nouwens, Marcel Borowski, Bjarke Fog, Clemens Nylandsted Klokmose

ACM DL link: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3313831.3376287

This was a participatory design research project between the authors and some biomolecular nanoscientists. Their question was “what is the role of computation in the work of these biomolecular nanoscientists,” where the work in question was san RNA folding problem. They identified three key themes:

- Computational culture: this kind of field uses “black box” machines a lot, and because they’re working on the frontier they’re often using either well-supported tools or tools that they built themselves—there’s very little in between. The scientists are also not trained in CS.

- Computational environments: some other struggles come from managing execution environments. The scientists often have difficulty getting software to work at all, and when running into difficulties that they view as insurmountable, they often simply give up.

- Computational disempowerment: the above leads to a feeling of computational disempowerment, which manifests itself as chronic helplessness and self-blame. When things went wrong, they have no idea what to do. Sometimes, the scientists report knowing that there are better ways to do something, but not knowing how to learn about those (or not having the time to learn).

There’s a computational media spectrum, which on one end has scripts in a terminal (which have a high ceiling and high complexity) and on the other has applications (which are self-contained and often don’t allow for computation at all). Notebooks lie in the middle, but still closer to scripts & terminals, and the authors designed something in the gap between notebooks and applications.

After user testing, they landed on these design principles:

- shareability: rather than real-time collaboration, which the scientists rarely needed, consider shareable, self-contained computational environments. Traces of activity & action-consequence (when you do something, you can see what happens) are helpful, too.

- malleability: rather than low-level code tinkering, consider larger scale software transformation or controlling “what is malleable when”

- distributability: offloading heavy processing to remote servers is useful, allowing scientists to e.g., close their computers at night.

- computability: executing code wasn’t as helpful as agnostic mixing of multiple programming languages.

“Learning how to code” is a myopic approach if the medium in which we use computation does not evolve along with it. (But what that medium looks like is up for debate.)

This is great—it hits on an important idea that I think is often ignored. I’ve noticed this when helping teach people to program; it’s one thing to write Python in VS Code and hit the “play” button to run it, but when packages aren’t installed or the students have to debug something in their terminal, the students will often panic. Abstracting “programming” to mean more than the code itself is important.