Measuring the (un)fairness of a predictive model is challenging work. This NeurIPS paper motivates and defines two concepts for this, “equalized odds” and “equal opportunity.” It then develops a a post-training framework to induce these new notions of fairness onto a trained model.

Authors: Moritz Hardt, Eric Price, Nathan Srebro

Link: arXiv, blog post, a cool interactive visualization

Background and motivation

Fairness in machine learning is important, and figuring out how to avoid discrimination is an active area of research. There are two common, but flawed, approaches:

- “Fairness through unawareness” (ignoring race, gender, etc.) obviously doesn’t work, because of proxy variables (like zip code encoding race).

- “Demographic parity” (requiring that a decision be independent of a protected class) also does not work. It doesn’t ensure fairness, and lowers the utility of our classifier.

(For the limitations of demographic parity the authors cite Dwork et al. 2012, which Hardt also worked on.)

Taking a step back, the discrimination problem assumes a distribution over a target Y, features X, and protected attribute A. The goal is to construct Y’ = f(X, A), that predicts Y. This paper formalizes the idea of Y’ not discriminating with respect to A. (The paper uses $\hat{Y}$, but Y’ is easier to type in plaintext.)

To formalize the notion of non-discrimination, the authors propose a new “equal odds” / “equal opportunity” framework. It can be constructed from an already-trained model, and in theory incentivizes better features (which are correlated with the target, not the protected class). That sounds promising.

Definitions: equalized odds and opportunity

Equalized odds: a predictor Y’ satisfies equalized odds with respect to A and an outcome Y if Y’ and A are independent conditional on Y. This allows Y’ to depend on A only inasmuch as A contributes to Y. Formally,

$$ P\left[Y’ = 1 | A = 0, Y = y\right] = P\left[Y’ = 1 | A = 1, Y = y\right] ; y \in \{0, 1\} $$

When y = 1, this requires that Y’ has equal true positive rates across A = 0 and A = 1. When y = 0, it requires equal false positive rates.

(If there’s a score $R \in \mathbb{R}$, then R can satisfy equalized odds if R is independent of A given Y.)

Equal opportunity is a relaxation of equalized odds for only the positive outcome, which is usually thought of as “advantaged” (getting a job, receiving a loan).

$$ P\left[Y’ = 1 | A = 0, Y = 1\right] = P\left[Y’ = 1 | A = 1, Y = 1\right] $$

How to achieve this

We now explain how to find an equalized odds or equal opportunity predictor Y* derived from a, possibly discriminatory, learned binary predictor Y’ or score R. We envision that Y’ or R are whatever comes out of the existing training pipeline.

(As before with Y’ instead of $\hat{Y}$, I’m using Y* where the paper uses $\widetilde{Y}$.) I’ll now copy some notation directly from the paper:

This basically says that, to satisfy equalized odds, both the true and false positive rates must be equal regardless of whether an individual has the protected attribute A. Meanwhile, for equal opportunity (which we recall as a weaker version of equal odds), only the true positive rates must be equal

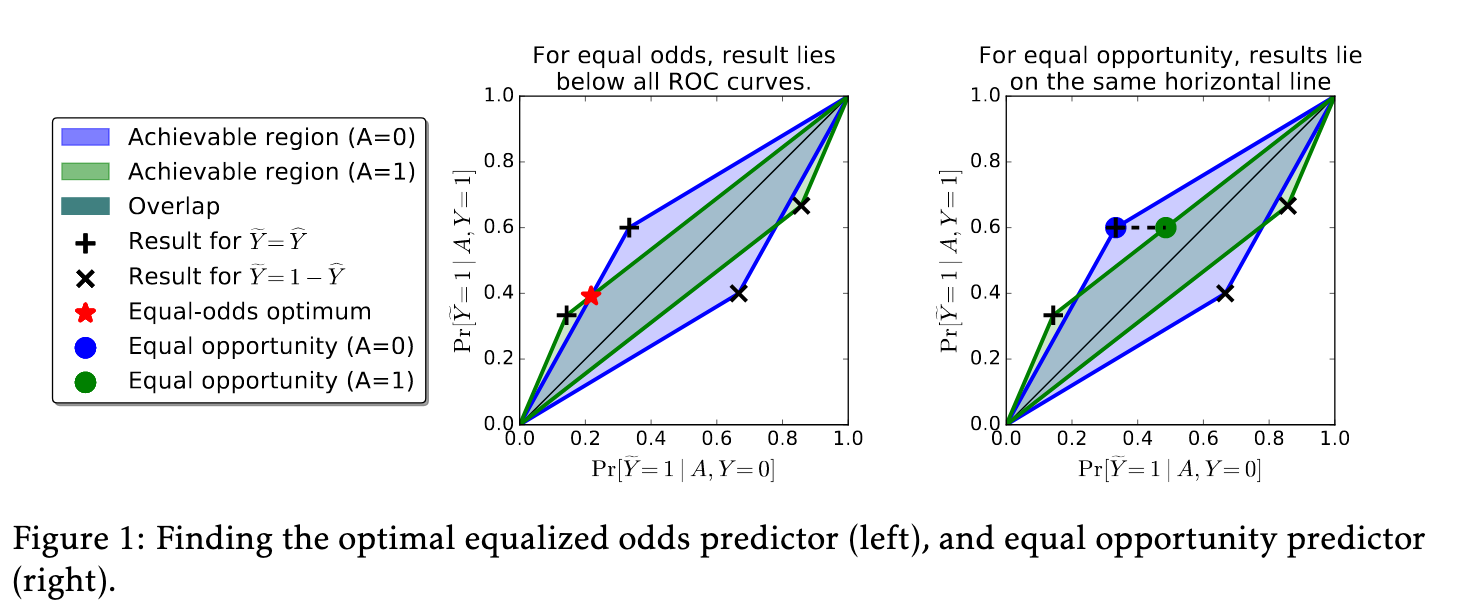

This has a geometric interpretation:

I spent a lot of time staring at this figure and only kind of understand what’s going on, so I can’t go into too much more depth here. But finding the equalized odds predictor given this formulation is a linear program.

Deriving the equalized odds predictor from a [0, 1]-valued score function is harder, but still computationally tractable.

Then there’s something about Bayes optimal predictors, which I skipped reading. The main point, from the introduction, is that “the Bayes optimal non-discriminating … classifier is the classifier derived from any Bayes optimal … regressor using our post-processing step.” This allegedly helps justify why they introduce a post-training process here (because you aren’t impacting Bayes optimality?).

Implications and case study

The authors point out that no “oblivious test” can resolve certain scenarios, which have the same joint distribution but different interpretations with respect to fairness. What does that mean? That “no test based only on the target labels, the protected attribute, and the score would give different indications … in the two scenarios.” This is a shortcoming of not only equalized odds, but every such “oblivious test.”

The authors then apply this framework to the FICO credit scores prediction problem. They consider a four-value protected class (race), which I particularly appreciate for not being the most trivial (binary) case possible. They show how to construct an equalized odds and equal opportunity classifier, then consider its implications.

Thoughts

I think this paper did a great job of explaining the mathematics behind its models. The authors introduced new ideas conceptually and then mathematically. I am confident that, had I spent more time on this paper, I would have understood the results in a little more depth.

With all this said, I didn’t. I didn’t spend enough time on this paper to really grok all of the math happening here. I think the most interesting parts were:

- the definitions of equalized odds and equal opportunity

- the result that a classifier satisfying those can be constructed from any other classifier, after training is complete

- the result that “oblivious tests” are sometimes unable to distinguish between very different (with respect to fairness) scenarios

- that this is aligned with the usual machine learning goal of high accuracy.

- that this incentivizes collecting features that predict the target, rather than protected-attribute-proxies.

The authors note that this framework is not to be considered a proof of fairness, but rather a measurement of unfairness. This is an important distinction to make, because “fairness” exists in a broader social context.

I am influenced here by one of the pieces I read last week, titled AI bias and the problems of ethical locality. Among other things, this argued:

The practical locality problem also indicates that employing more procedurally fair AI systems is not likely to be sufficient if our goal is to build a fair society. Getting rid of the unfairness that we have inherited from the past—such as different levels of investment in education and health across nations and social groups—may require proactive interventions. We may even want to make decisions that are less procedurally fair in the short-term if doing so will reduce societal unfairness in long-term.

This is out of scope for the paper, but it’s worth thinking about the ways in which non-discrimination frameworks might not be enough. Specifically, mathematical models of this problem do not address the issue of power, which is central to questions of AI fairness.

Finally, I think it’s particularly notable that all of this can be achieved with a simple post-processing step. This step “could even be carried out in a privacy-preserving manner (formally, via Differential Privacy),” which is a really interesting thought! I think a tough, but satisfying project, would be a machine learning project applying both differential privacy and equalized opportunity.