How do fandom communities move from platform to platform over time? What causes people to leave a platform in favor of a new one? This paper dives into community migrations in the fandom community.

Authors: Casey Fiesler, Brianna Dym

Link: PDF

Background

It is a reality of the internet that online platforms come and go over time. But platforms host communities, and when platforms shut down, communities go through a “forced migration” to another platform. Studying these migrations is the focus of this paper.

There can be other reasons for migrations besides platforms shutting down. Disagreement with a platform’s content or moderation policies (as has happened on Reddit), an unpopular site redesign, or feeling like the community doesn’t fit in can all cause migrations, too. Of course, these come with costs (incompatibility, loss of history, learning curves, losing members).

This paper studies a community of digital migrants, that of “transformative fandom,” which are (loosely) communities of media fans who “create, share, and discuss fanworks based on existing media.” They focus their studies on fandom on the platform Archive of Our Own (AO3).

Methods and data collection

The authors’ methods included:

- 28 semi-structured interviews, focusing on the platform Archive of Our Own (AO3)

- 1,886 survey responses, designed in response to the interviews

The interviews were with 28 fandom participants who used AO3, focusing primarily on those who had been involved in fandom for a long time (mostly 10+ years).

We asked participants about their history in online fandom, what their experiences and communities were like on each platform they used, and (because AO3 was formed in the wake of a significant fan migration) what their experiences were in moving between platforms.

The survey expanded on themes found in the interview, as is typical with these types of studies. It mapped out which platforms participants had used and when, then asked them to expand on their experiences with each. Participants answered questions on fandom-related activities on different platforms, what drew them there, and what made them leave.

The community demographics are worth noting; consistent with typical fandom demographics, respondents were overwhelmingly female and non-heterosexual. 80% of survey respondents stated (in a voluntary, free-text field) that they were female, and only 24% identified as heterosexual. It’s worth keeping in mind that the fandom community looks very different than a lot of the rest of the internet does.

Platform migrations

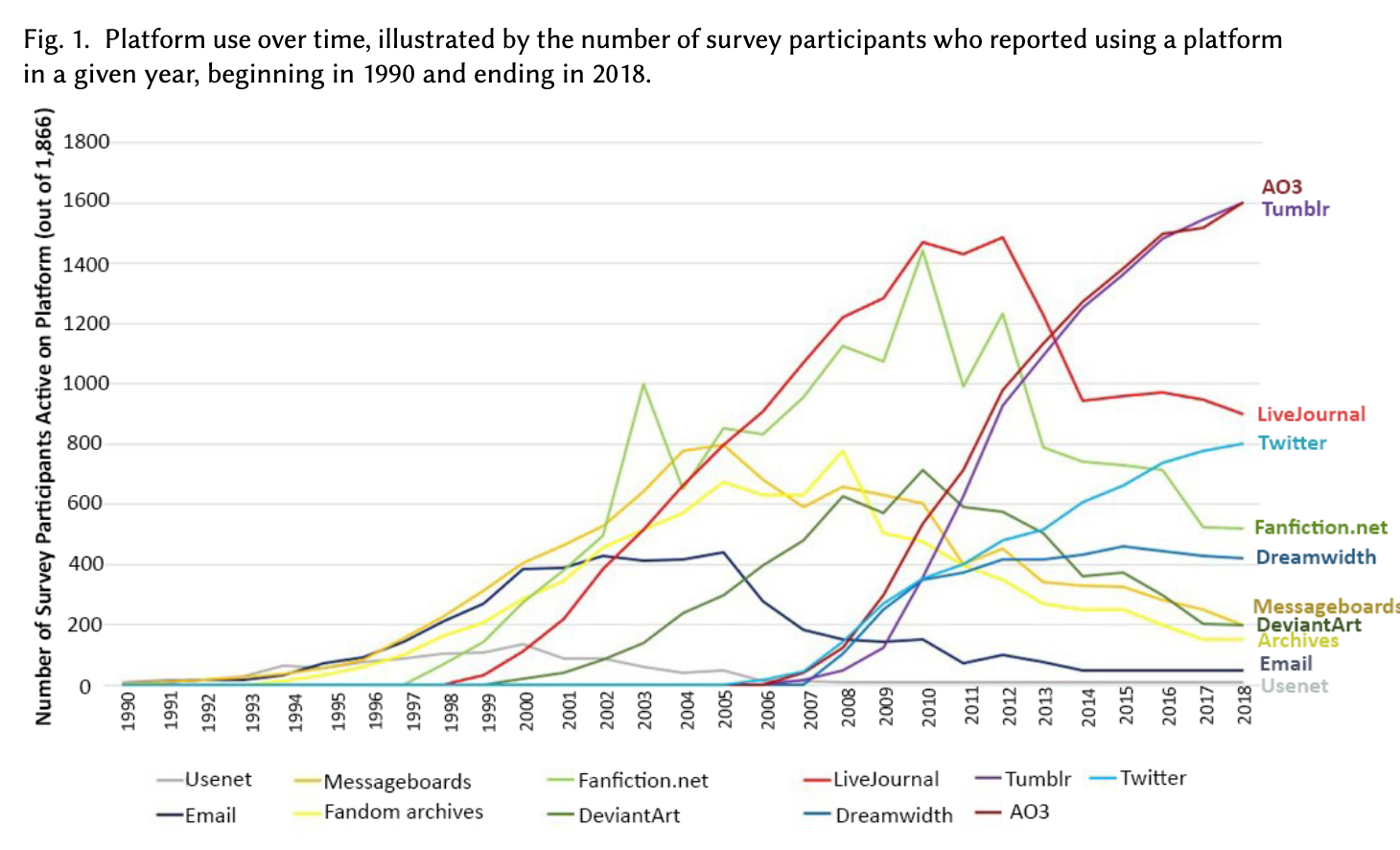

This plot is amazing—

It captures so much:

- Usenet being the original fandom platform

- AO3 and Tumblr rising almost simultaneously

- The rise and fall of LiveJournal and Fanfiction.net

- The slow collapse of specialized message boards from their peak in 2004 (!)

The paper studies these migrations in depth, starting with reasons for migration.

Platform-based reasons include features & design, values & policies, and content. Content was most important in people deciding to join platforms, but they were most likely to leave because of design changes, policy changes, or (most often) the emergence of a new, better platform.

One of the most interesting ideas was the idea of design changes as an attack. This was the subject of a CHI 2011 paper, Redesign as an Act of Violence. (I’m thinking about this a lot in the context of reddit.)

Community-based reasons were common, too. These could be to join a new community or to follow an existing community somewhere else. “These findings underlie that a huge contributor to migration is that people follow their friends and communities.” This causes natural snowball effects, but can also create “static chicken” (lol) where no one is willing to move first.

What about the consequences of migrations?

Technical challenges primarily consist of migrating content, where “something always ends up lost”—a major issue in creative communities like fandom. “Migration has really messed with our collective sense of fandom history,” one participant wrote.

Social challenges include communities splintering over time, because of people refusing to move or people becoming harder to find. This contributes to the decline of communities, and one participant likened these declines as “watching a shopping mall slowly go out of business.” This causes social fragmentation or splintering.

The opposite occurs, too; “another source of problems is when communities that might have been more isolated are thrown together,” which happened as otherwise disparate subcommunities consolidated onto the same platform.

Discussion

What can we learn from this? Quite a bit! This paper informs platform design for fandom communities, what the role of commitment in community migration is, and how value clashes can contribute to migrations.

By laying out the reasons that fans left platforms in order to join others, this work illustrates a number of potential failure modes for online platforms, as well as factors that contribute to success.

And later: “For example, the critical mass problem for starting an online community looks very different when the community itself is not starting from scratch but rather relocating onto a new platform.”

Barriers to migration often include “there’s nowhere better to go” (shown in the surveys full of people who hate Tumblr but stay there!). The authors highlight that the near-simultaneous rises of AO3 and Tumblr were caused by complementary feature sets: AO3 for archival and searchability, and Tumblr for ephemeral socialization.

What about designing for migration?

Though our findings might suggest guidance for the design of platforms for the specific community of fandom users, they also suggest some principles relevant to online communities more generally:

- “Leaving” a platform does not necessarily mean leaving a community, and may be more about relocation than exiting;

- Users often join new platforms with deep experiences in others, which can impact their expectations for and subsequent experiences of a new platform; and

- There are opportunities for the creation of new platforms that take advantage of the shortcomings of or attrition from others.

Taken together, these also suggest the importance of designing with migration in mind. Though fandom has provided an early example of many migrations over time, it is also likely that as the number of platforms in our social ecosystem continues to increase, whole communities leaving and joining platforms will become more common.

(2) is most interesting to me; the idea that platforms should consider users joining “with their bags packed from elsewhere” is so powerful to me. The duality of online communities being inherently transient, but as a result sometimes platform-agnostic and longer lasting, is a powerful concept.

This is useful for understanding platforms more broadly, not just in the context of fandom. Why don’t people leave Facebook, the authors ask? Because there’s nowhere better to go—nowhere else that’s “good enough,” where all their friends and family are. The key value in this work was digging into what that “good enough” really means.

Personal experience

What an interesting paper!

As our digital communities grow more and more complex, we should try to better understand what connects an online community beyond the platform where it is embodied. Communities rarely emerge in a vacuum, carrying with them a history of previous relationships and community memberships [53].

I love thinking about online communities and their lifecycles. This work shed light on exactly that—how communities come and go, and how their users move from platform to platform, forever in search of an inevitably transient digital home.

My personal experience with this paper’s subject is the reason I chose it for the first CSCW paper to read. I wrote about one fandom community, back when I was building the Pokemon Mystery Dungeon rescue project.

One of the ideas that I wrote was about the community we built:

Today, the communities that I mentioned no longer exist. GameFAQs is slowly dying; now there are more scattered communities on various platforms, and an active Discord server. In the age where people are Extremely Online it’s no longer the case that a single website could have the same effect that it once did.

I don’t actually know that this is true, after reading this paper and reflecting on it. Yes, the online communities that I mentioned no longer exist. But fragments of the community did migrate to other platforms, which I mentioned:

And so, as happens on the internet, several dozen of us—the most active among us—migrated to another forum. InvisionFree was a popular free forum host, so we made our own community there and let it grow. We had a xat chatbox (TIL xat still exists) at the bottom of the boards. A few years later, we migrated to Zetaboards, then when it was killed off, created a Skype group, and now a Discord server.

The community still exists in some form, even though the platforms are lost to time. Fiesler and Dym perfectly captured my feelings in their Social Challenges section:

Many participants spoke of how communities inevitably splinter, because some members will refuse to move, or because old friends become difficult to find. Beyond losing content in a technical sense, this also means losing social connections.

I didn’t expect this paper to be so poignant, but it has me reflecting on my internet experiences over the past 15-ish years. Online communities are so powerful; the questions of how we design them, and how they do and don’t last, are so interesting to me.